Chapter 1: The Islamic Worldview

This section outlines the conceptual framework of the Islamic worldview. At its centre stands Tawhid, which is not merely a theological statement, but the foundation upon which the entire Islamic paradigm rests. Islam is not a collection of isolated beliefs, nor a linear checklist of rituals, rules, and doctrines. It is a coherent, interconnected worldview that shapes how we understand reality, purpose, morality, society, and the human self.

To grasp Islam as a lived civilisation rather than a set of fragmented practices, we must first understand the worldview that underpins it. This post establishes that foundation. Every post that follows in this section builds upon this framework, allowing us to explore the Islamic paradigm with clarity, coherence, and depth.

Before we talk about strategy, geopolitics, or revival—We must first ask:

What is the essence of Islam and what have we added to it or replaced it with?

Because real change won’t happen by just talking about structures or politics, it begins by challenging the very mental and cultural frameworks we carry within us and out of which we operate.

The “Operating System” Behind Your Understanding of Islam

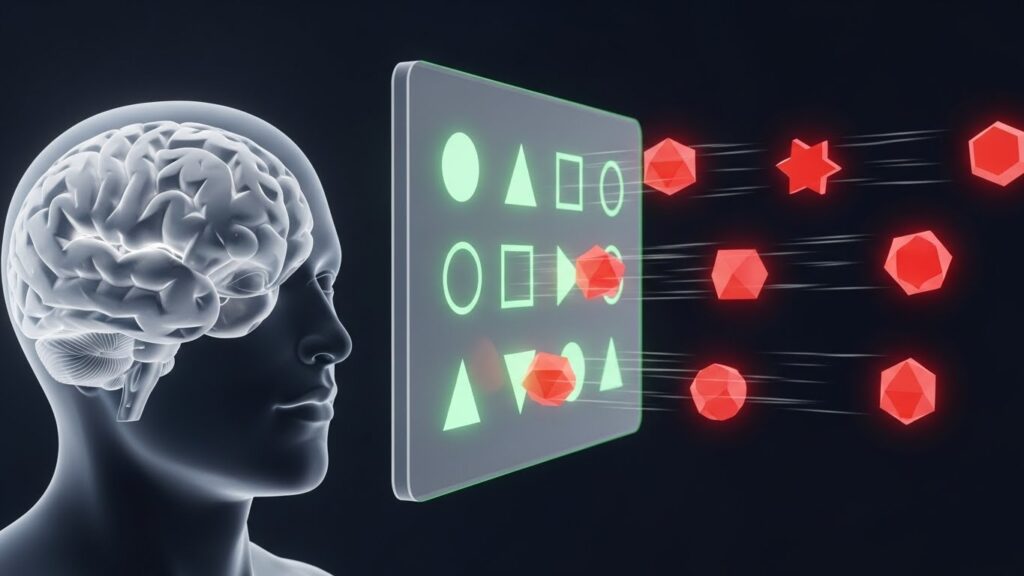

This brings us to a concept in psychology known as a schema.

A schema is the internal operating system through which you interpret everything including Qur’ān, Sunnah, politics, identity, morality, even what you think “Islam” is. It’s built from years of culture, upbringing, schooling, social pressure, colonial conditioning, personal fears, and selective religious teachings. Over time, this mixture hardens into a “default Islam” that you operate from, one you rarely question because it feels familiar, safe, and normal.

So when a new idea comes to you, especially one rooted in authentic Islamic sources, your mind doesn’t assess it on its own merit. It first asks a different question entirely:

Does this fit into the worldview I already have?

If it fits, you welcome it. If it doesn’t, you reject it, often instantly, without reflection.

This is exactly why the shape-sorter analogy matters. Your schema functions like that sorter:

- Ideas that match your pre-existing shapes slide through effortlessly.

- Ideas that challenge your worldview bounce right off — not because they’re wrong, but because they don’t fit.

And here’s the uncomfortable part:

Most Muslims never ask the only question that matters:

Is it the idea that’s wrong, or is it my schema that needs to evolve?

That’s where the crisis lies. We mistake the Islam in our head for the Islam revealed by Allah (swt).

And when a verse or hadith cuts across our comfort, our habits, our cultural expectations, or the diluted, domesticated form of Islam we inherited, what do we do?

We shrug it off. We rationalise it away. We soften it. We ignore it. We bury it under “context.” Or worse, we reject it outright but in a sophisticated enough way that we don’t feel guilty about it.

This is cognitive dissonance in its rawest form: the collision between the truth you recognise in your fitrah and the worldview you’ve been conditioned into. That friction is supposed to wake you up. Instead, most people retreat from it, because adjusting your schema means dismantling parts of yourself—your identity, your assumptions, your comfort zones.

When you encounter something (a Qur’anic command, a prophetic expectation, a historical reality, a political principle of Islam) that contradicts your worldview, you have two choices:

- Reject the idea to protect your schema.

- Rebuild your schema to align with truth.

Most choose the first. Real transformation only begins with the second.

Clinging to option 1 is why the Ummah remains stuck because we choose comfort over courage, tradition over truth, and acceptance over Taqwa.

If you don’t correct the schema, the revelation itself becomes filtered and distorted.

So the invitation is simple:

Open your mind. Let the truth reshape you rather than forcing the truth to fit you.

The Revolutionary Power of Tawhid

The first step in the Missing Muslim Narrative begins with returning to the Islamic worldview: the way Islam teaches us to see reality, power, purpose, and our place in the world.

At the heart of that worldview stands Tawhid.

Tawhid is far more than an abstract belief in the Oneness of God. It is the organising principle of our lives. It reshapes how we understand society, justice, authority, economics, knowledge, identity, and our very sense of self. Every structure we build, every moral choice we make, every collective project we pursue—all of it flows from this single truth.

But to grasp the full force of Tawhid, we cannot approach it as a detached theological idea. We must return to the world into which it was first revealed. A world defined by hierarchy, tribal supremacy, economic exploitation, and a religious order built to preserve the status quo. In that society, Tawhid was not merely a spiritual statement—it was a revolutionary intervention. It dismantled the ideological foundations of oppression, re-ordered power, and redefined what it meant to be human.

Only by understanding that original context can we understand why Tawhid is still the most subversive, liberating, nation-shaping idea we possess—and why reclaiming it is the foundation of our struggle today.

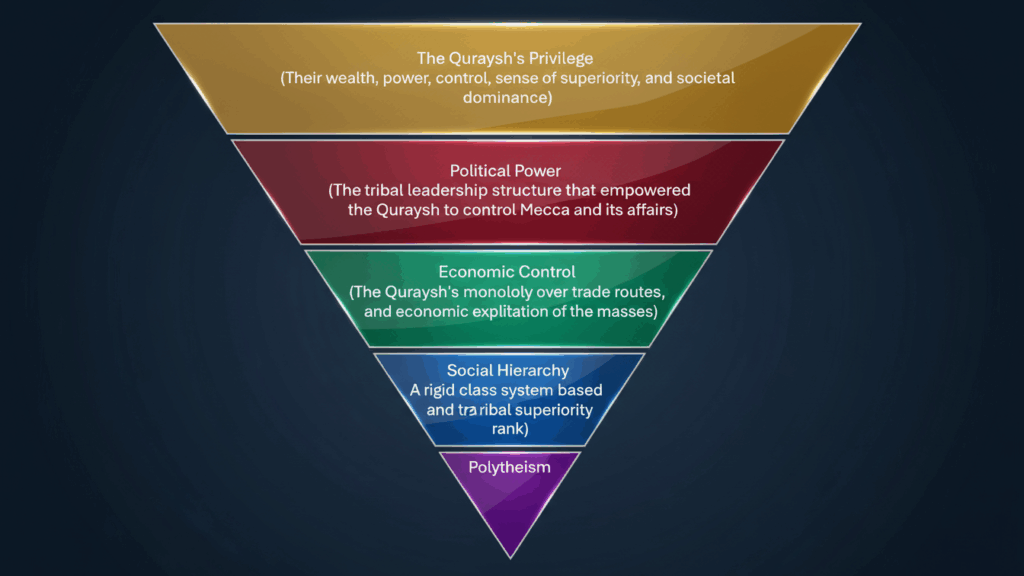

Pre–Islamic Arabia was a polytheistic society meaning they believed in multiple gods, and this belief in multiple gods had deep–seated socio–economic and political implications. The very structure of their society was intertwined with the idea of multiple gods, and this cosmology contributed to an oppressive, unequal, and corrupt system.

What many may find surprising is that, even in their polytheism, the Arabs of the time recognised Allah (swt) as the Supreme Being. However, they viewed Him as too distant and transcendent to be approached directly. Instead, the people sought the intercession of lesser gods, intermediaries such as Allat, Al–Uzza, and Manat—goddesses believed to be Allah’s daughters. Each god had its idol, scattered throughout the Arabian Peninsula, marking territories of devotion and control.

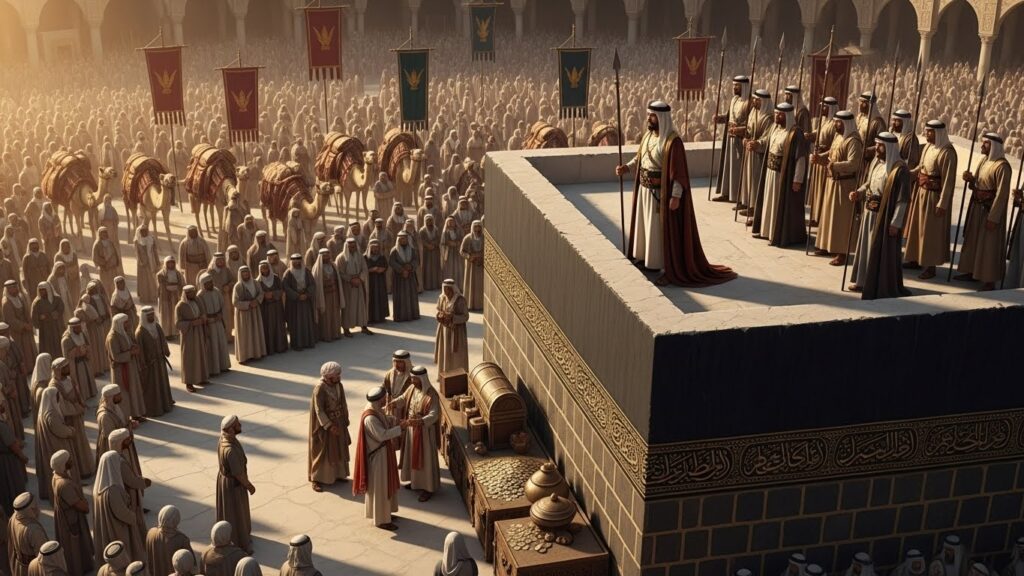

This polytheistic framework wasn’t just spiritual—it was political and economic. Religious devotion to these idols was intertwined with the social hierarchy, and the powerful tribes of Mecca, particularly the Quraysh, leveraged this belief system for their own benefit. The most important religious site was the Ka’ba, a sanctuary housing idols from all over Arabia. Control of the Ka’ba equated to both spiritual and political control, and this is where the Quraysh exercised their power.

In the late fourth century, a man named Qusayy rose to prominence by consolidating power in Mecca. His genius lay in realising that whoever controlled the Ka’ba controlled the city. By uniting feuding tribes under his leadership—through strategic marriages and alliances—he secured the Ka’ba and declared himself the “King of Mecca.” This was not merely a religious title; it was a claim to supreme political authority in the region.

The power Qusayy wielded stemmed from his exclusive right to manage the Ka’ba’s affairs. He controlled access to the sanctuary, governed the distribution of resources, and even directed the banners for war.

Through these mechanisms, Qusayy created a hierarchy within Mecca itself, dividing the city into inner and outer districts, with the closer one lived to the Ka’ba, the more prestigious one’s status became. His own house was attached to the Ka’ba, further symbolising his direct connection to the divine sanctuary.

But his consolidation of power didn’t stop at religious authority.

By gathering the idols of various tribes into the Ka’ba, he transformed Mecca into a centralised place of worship, to which every tribe felt obligated. This not only gave him religious dominance but also economic leverage, as Mecca became the focal point of pilgrimage, trade, and commerce.

Pilgrims and merchants flocked to Mecca, and Qusayy imposed a tax on goods entering the city during the pilgrimage season. The Quraysh controlled the wealth generated by these activities, thus ensuring their dominance not only spiritually but also economically.

The Quraysh’s power was further entrenched by their strategic manipulation of the Ka’ba’s sanctity.

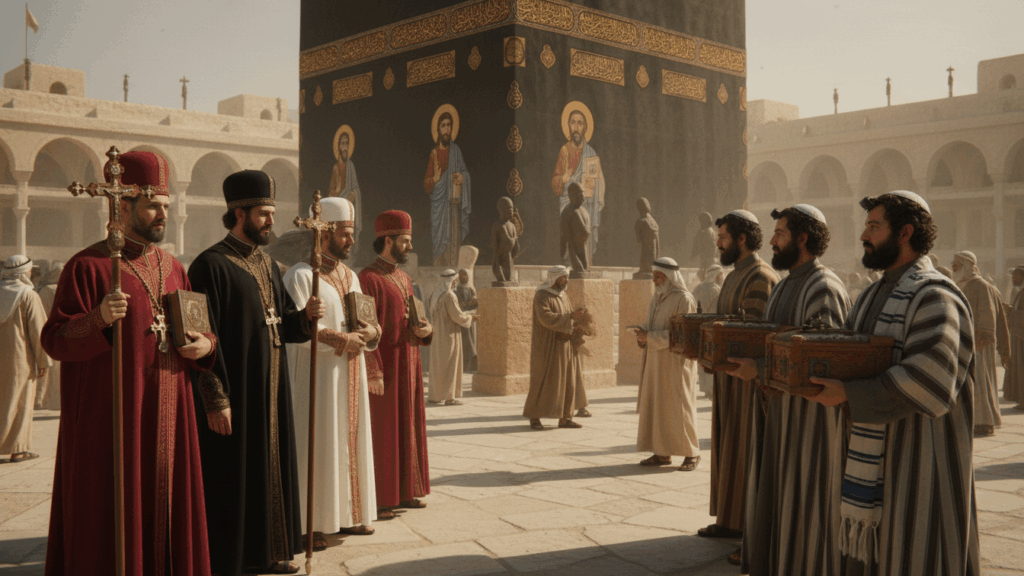

The Ka’ba housed representations of important figures from various religions, including a painting of Jesus and an idol of Abraham, revered by both Christians and Jews. By accommodating the beliefs of multiple religious groups, the Quraysh ensured that the Ka’ba became a shared sacred space, further elevating their influence across religious divides. By blending sacred and strategic, the Quraysh turned faith into a currency of control.

Through the control of pilgrimage and trade, the Quraysh amassed unprecedented wealth. This wealth concentrated in the hands of a few powerful families, disrupted the traditional tribal ethic that had once been the fabric of Arabian society. Arabia lacked any central governing body or absolute moral framework anchored to a scripture; it was instead organised around tribal affiliations. The only semblance of legal order was the law of retribution—an eye for an eye, a life for a life, or the payment of blood money. Each tribe had a ‘Shaykh’ responsible for maintaining this fragile peace.

However, this system of retribution was deeply flawed. It only protected those within the tribe, leaving those outside its protection—widows, orphans, and members of less powerful tribes vulnerable to exploitation. Crimes committed against these individuals were rarely punished. Theft, murder, and assault were not necessarily considered immoral unless they threatened the tribe’s stability. The wealthy and powerful tribes, therefore, operated with near impunity, while those of lesser status had little recourse for justice.

This inequality led to the accumulation of power and wealth among the few ruling families. Through intermarriage and alliances, these families solidified their dominance, creating a rigid hierarchy that was nearly impossible to penetrate. For those outside these elite circles, life in Mecca was brutal. Widows, orphans, and the poor often had no choice but to borrow money from the wealthy at exorbitant interest rates, plunging them into inescapable debt, poverty, and even slavery.

Imagine, for a moment, the psychological and social impact of such a system.

This was a society where one’s status, wealth, and power were predetermined by birth, where the elite controlled both spiritual and material life, and where the majority languished in poverty or servitude. At the foundation of this entire socio-political and economic structure was polytheism. Far from being a purely spiritual matter, polytheism was a tool that legitimised oppression, justifying and reinforcing the hierarchies that sustained the ruling elite’s dominance.

So picture for a second, what would happen if a man comes along and simply utters the words La ilaha ilallah—there are no gods except Allah. What are the implications of Tawhid to a system of oppression and exploitation built upon the beliefs in multiple gods? And this too, to a community that already believed in Allah (swt) but had concocted multiple gods as intermediaries to uphold their power structure.

The belief in Tawhid was more than a theological assertion, it was a direct challenge to the power structure of that time—and the Quraysh leadership knew this.

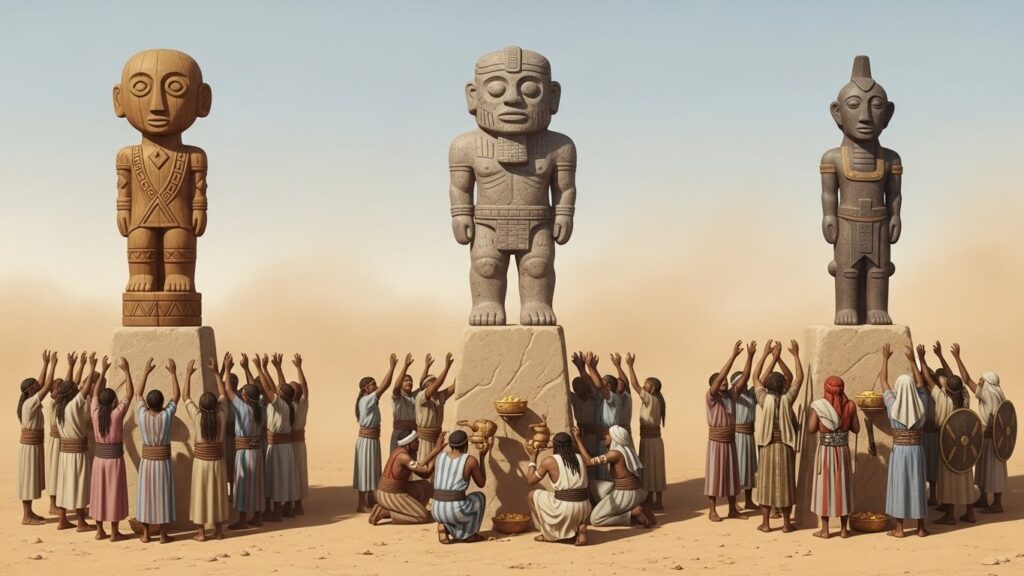

Let me further demonstrate the impact of polytheism visually in a different way. When a society believes in multiple gods, it does more than diversify spiritual practices, it reshapes the entire social order.

Each tribe attaches itself to a different deity, and over time, these gods begin to reflect the power, status, and ambitions of the people who worship them. The stronger the tribe, the more “important” their god becomes.

The weaker the tribe, the more insignificant their god is viewed. What begins as a difference in belief becomes a difference in worth.

This is how polytheism divides people into separate groups, each competing for the favour, authority, and legitimacy of their god. And as each god gains or loses prominence, the people tied to them rise or fall accordingly. A spiritual hierarchy becomes a social hierarchy. Some tribes stand above others, not because they are more just or more moral, but because the god they worship is considered higher, stronger, or more central.

Belief in multiple gods creates a civilisation where the sacred is weaponised, elevating some, diminishing others, and entrenching systems of subjugation and exploitation. It turns religion into a ladder of power, and people into rungs upon it.

Think of all the oppression that has occurred historically, the foundation of it was inequality.

When blacks where enslaved, it was because they were projected as inferior both intellectually and morally. European colonisers often used distorted interpretations of Christianity and early “scientific” racial theories to claim that Black people were inherently suited to servitude, less rational, and spiritually deficient.

When Muslims in Bosnia were massacred during the 1990s, they were systematically portrayed as backwards, threatening, and inherently violent, painted as “others” who did not belong to European society. This narrative dehumanised them, making the atrocities—from ethnic cleansing to mass rapes—seem like a defensive or necessary action in the eyes of perpetrators.

Indigenous peoples in the Americas were depicted as savages, primitive, and incapable of governing themselves, justifying colonisation, land theft, and cultural eradication.

Jews in Europe were labelled as greedy, subversive, or conspiratorial, forming the basis for centuries of persecution, discrimination, and ultimately the Holocaust.

Irish under British rule were described as uncivilised and incapable of self-rule, used to rationalise famine policies, land confiscation, and forced labour.

Rohingya in Myanmar are portrayed as illegal, foreign, and a threat to Buddhist society, legitimising persecution, displacement, and violence.

The root of systemic evil in this world is inequality.

Tawhid declared The Oneness of God and under Tawhid all of mankind is equal in the eyes of God.

The prophet pbuh said: “People are equal like the teeth of a comb. There is no superiority of an Arab over a non-Arab, nor of a non-Arab over an Arab; nor of a white over a black, nor of a black over a white — except by taqwā (piety, God-consciousness).” [Al-Tirmidhī Hadith 3270]

Here, equality is not a philosophical idea, it is a divine truth. Every worldly hierarchy collapses. Lineage, tribe, race, class, and colour hold no weight. The only differentiating factor is character, and this is the one criterion that cannot be used to justify oppression, because it cannot be inherited, monopolised, bought, or weaponised. It is measured by God alone.

Tawhid therefore dismantles every human attempt to elevate one group above another. By rooting dignity in piety rather than power, it creates a moral order in which exploitation has no legitimacy, and equality becomes the foundation of true freedom.

Why “One God” Is Not the Same as Tawhid

It is also important to recognise that the mere belief in “one god” does not automatically produce these practical implications. Unity in number alone is not what transforms society.

Tawhid is not simply the idea that God is singular, it is the declaration that this One God is utterly unique, unlike anything in creation. He does not beget, nor was He begotten. He has no physical form, no image, no embodiment. He transcends space, time, and all limitations.

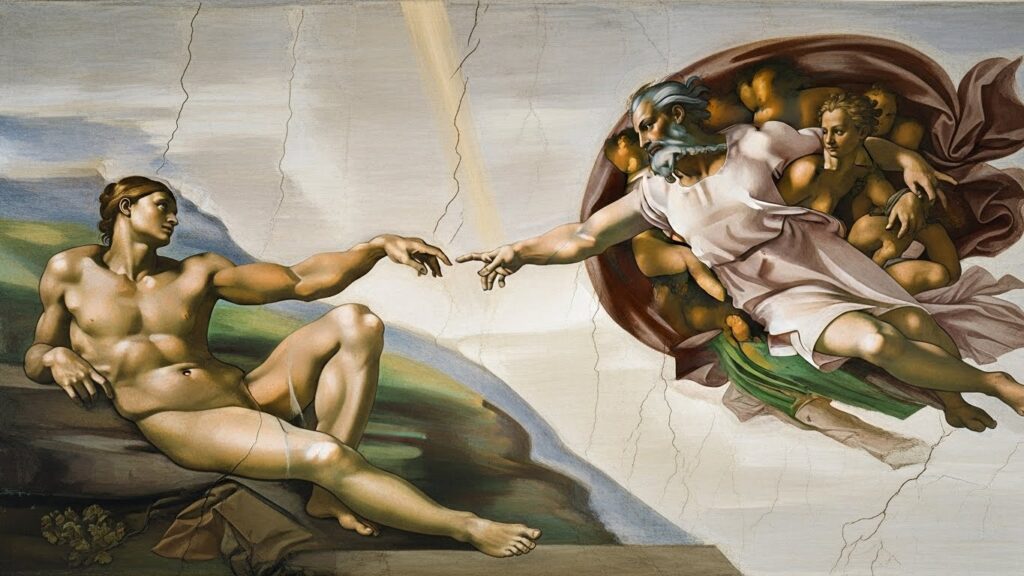

Now imagine if this were not the case.

Imagine if God had a physical shape—people could carve statues resembling Him, and whoever controlled those images would claim authority and superiority over others.

Then those who resembled that form could claim they were made “in His image,” elevating themselves above everyone else. The belief itself would become a justification for hierarchy, privilege, and dominance.

As in the well-known artistic portrayals within Christian tradition, where God is shown as an older white man reaching out to Adam. Such imagery has historically been used to elevate one racial group above others. If God is presented as looking like a particular people, that group can claim divine likeness, superiority, and moral authority. And indeed, this idea was exploited to justify slavery, colonisation, and the subjugation of non-white populations across the world.

Tawhid removes all of this. By establishing that God is unlike anything in creation, it prevents any group, tribe, race, or class from claiming divine endorsement or superiority.

Tawhid Establishes Equality; Equality Creates Freedom

Let’s return to Tawhid and its practical implication: equality.

If inequality produces oppression, then equality produces freedom, not only physical freedom, but far more importantly, mental and moral freedom. Tawhid liberates a person from every false hierarchy that claims dominion over them.

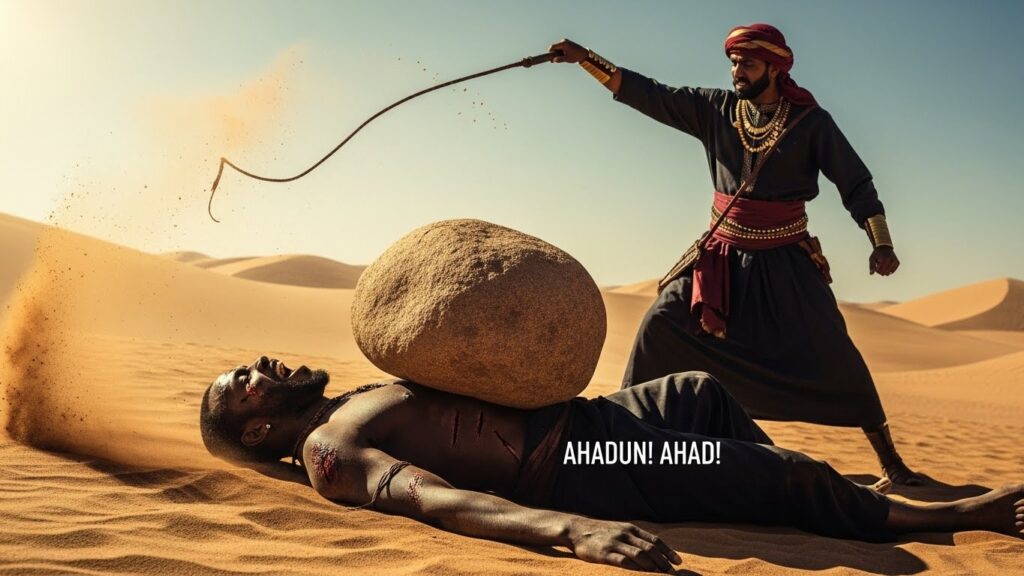

Nowhere is this more visible than in the story of Bilal (ra). A man born into slavery, stripped of status, protection, and voice—yet elevated by Islam to a position of honour.

When his oppressors demanded that he renounce Islam and return to their false gods, Bilal responded with unwavering conviction: “Ahadun Ahad”—”One, One.” Bound beneath the scorching sun with a massive boulder crushing his chest, Bilal’s body may have been enslaved, but his soul was free. His cry of “Ahadun Ahad” shattered the chains of fear and submission to anything but Allah (swt). His belief in Tawhid gave him a profound sense of liberation that no worldly power could strip away.

Let’s examine this through the lens of political and power dynamics. The Quraysh’s aim was not just to punish him, it was to turn him into a warning. As a slave without tribal protection, Bilal represented the most vulnerable in Meccan society. By breaking him publicly, they hoped to send a message that embracing Islam was an act of rebellion that would cost you everything. This was a calculated move on the narrative battlefield.

Their expectation was simple: relentless pain would force him to backpaddle, proving that defying the social order was futile. But Bilal’s defiance had the opposite effect. His repeated cry of Aḥadun Aḥad under unbearable torment became a rallying point, a living testament to the depth of faith Islam could inspire. Instead of frightening people away, it stirred curiosity: What is this truth that makes a man endure so much for it?

His tormentors tried to break him, not only to enforce submission but to preserve their ideology of dominance. The Quraysh’s idols were not just objects of worship but instruments of control, tied to the hierarchy and privilege they had carefully constructed.

When Bilal declared “One, One,” he rejected not just the polytheistic gods of the Quraysh but the entire system of false power they upheld. Pre-Islamic Arabia chained hearts to idols; Tawhid shattered those chains and changed the course of history. Mentally, spiritually, and ideologically, Bilal was no longer a slave to his master or to the oppressive social order. Instead, he submitted entirely to Allah (swt), the source of all freedom and the ultimate master.

This shift in Bilal’s consciousness is profound. Though physically at the mercy of his torturers, his soul was liberated in a way his oppressors could never comprehend. His master, who held wealth, power, and authority in the material world, remained chained by ego, greed, and the delusions of worldly status. In contrast, Bilal, though beaten and humiliated, transcended these illusions and found true freedom—the kind that can only be attained in servitude to Allah (swt).

This posed a serious problem for the Quraysh. Continuing the spectacle of torture while Bilal remained unbroken undermined their image of absolute control. It chipped away at the fear that kept their system intact. The oppressed saw a man with nothing in this world still standing freer than his master—and that truth was dangerous.

Frustrated and unable to shatter his resolve, the Quraysh seized the opportunity to end the episode when Abu Bakr (RA) offered to purchase Bilal’s freedom. Accepting the offer allowed them to save face—they could frame it as a simple transaction rather than admit to a moral defeat in the public eye. But in reality, the damage to their narrative was already done. Bilal’s endurance had exposed the cracks in their power, showing that Tawḥid, once rooted in the heart, could not be broken by any chain.

Therefore, we see that the practical implication of Tawhid is equality, which naturally leads to freedom but not in the Western sense of indulging every desire of the nafs. This is a freedom that liberates the soul, allowing it to submit fully and sincerely to Allah (swt) alone. True freedom in Islam is not lawless indulgence; it is the alignment of our mind, body, and spirit with divine justice, morality, and purpose.

Tawhid calls us to reject not just physical idols but every construct that enslaves our hearts and minds, inviting us to live a life of true liberation.

The Forbidden J Word

Islam is unique in its stance on oppression. It is not enough that we ourselves avoid oppressing others, we cannot accept oppression, either. Muslims cannot remain passive in the face of injustice; we are obliged to resist it. This is a defining difference from the Christian teaching of “turn the other cheek” (Matthew 5:39). While that verse calls for patience, non-retaliation, and personal forgiveness, it primarily focuses on individual conduct, often encouraging believers to endure injustice with the promise that ultimate justice rests with God. Islam, by contrast, frames resistance as a collective, moral, and spiritual duty. Justice is not deferred to the day of judgement—it must be actively pursued.

Knowing that humans are equal and free does not make us truly equal and free. We must struggle for it in action, embodying it in our choices, systems, and governance. Think of it like learning to ride a bike. You can read every book on cycling, understand the physics of balance, and memorise all the techniques—but you will never truly ride until you get on the bike and start pedalling.

Believing in Tawhid plants the seed of equality, but a belief, on its own, does not transform the world. Knowing that all humans are equal and free does not make them equal and free. That truth must be defended, upheld, and embodied. And this is where Islam moves from principle to action. Once we recognise the oneness of Allah (swt), we must also recognise the responsibility that flows from it: we cannot allow oppression to stand unchallenged—within ourselves, within our communities, or anywhere in the world. This moral duty is the natural continuation of Tawhid.

This is where the concept of Jihad comes in. Yes, that five-letter word that is the most demonised and vilified across the globe.

At its core, Jihad is the struggle against oppression and injustice. Allah (swt) commands:

“And what is [the matter] with you that you fight not in the cause of Allah and [for] the oppressed among men, women, and children who say, ‘Our Lord, take us out of this city of oppressive people and appoint for us from Yourself a protector and appoint for us from Yourself a helper?’” (Surah An-Nisa 4:75)

The basis of Jihad, therefore, is to fight and resist oppression. Historically, once Muslims established themselves in Arabia, the focus of their military and political efforts was liberating the oppressed from unjust systems. Just as the Quraysh had created a political and economic structure to exploit, other empires and ideologies had done the same. Muslims conquered lands, dismantled oppressive structures, and left people free to live according to their own beliefs, with Islam serving as the moral framework rather than a coercive system. Forced conversions, often propagated in modern Islamophobic narratives, were neither normative nor sanctioned; the focus was always justice, protection, and equality.

What is particularly striking is that other communities recognised this unique element of Islam. For example, in medieval Spain, Unitarian Christians, who were being persecuted by the dominant Trinitarian majority, called upon Muslim rulers for protection. They understood that Muslims were committed to defending the oppressed, regardless of their faith, and that Islamic governance provided justice and refuge where other systems had failed.

The inherent anti-oppression nature of Islam has not gone unnoticed by global powers either. For example, during the Cold War, the United States recognised that Islam’s anti-oppression ethos could mobilise resistance against the Soviets in Central Asia. Through intermediaries like Pakistan, the CIA distributed copies of the Qur’an and other Islamic literature to populations under Soviet influence, knowing that its message of equality and resistance could incite rebellion against oppressive regimes. This demonstrates how the principles of Tawhid—equality, justice, and resistance to oppression—are so practically powerful that they have been leveraged even by external powers for political ends.

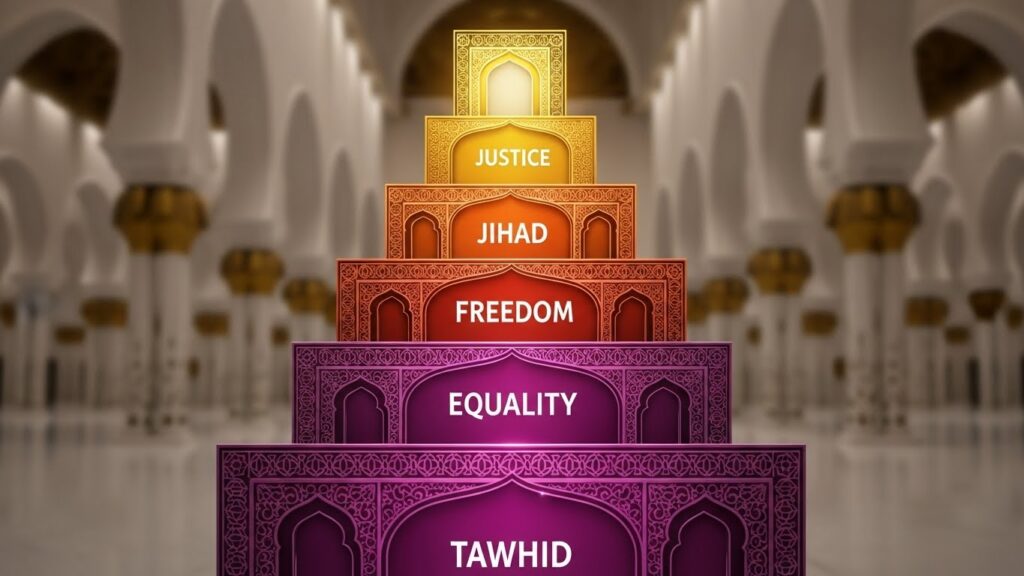

When we place all of this in context, the picture becomes clear: Tawhid births equality, equality demands freedom, and freedom cannot survive without resistance to oppression. Jihad is simply that resistance in its organised, principled, and disciplined form. It is the bridge between belief and justice. And justice is the highest manifestation of Tawhid in society—a world in which no human being is bowed before another, and all stand equal before their Creator.

Justice: The Highest Manifestation of Tawhid

When we, the believers, enjoin what is good and forbid the evil, or perform the higher expression of this concept—Jihad, to dismantle oppressive systems built upon inequality, the result is justice. Put simply:

The practical, real-world implication of Tawhid at the highest level is justice.

Justice is not a peripheral concern in Islam—it is intrinsically tied to the very concept of Tawhid, the belief in the Oneness of Allah (swt).

To make this unequivocally clear: even if the Prophet (pbuh) had received no revelation except the command to affirm Tawhid, that command alone would necessitate and obligate Muslims to uphold justice. Tawhid is not a detached theological idea; it is the foundation for moral, social, and political action. If we claim to believe in the Oneness of Allah, then the pursuit of justice is not merely encouraged—it is a necessary consequence of that belief. A faith rooted in Tawhid cannot coexist with injustice, inequality, or oppression.

Now, naturally, I hear you ask: if justice is truly woven into the very fabric of Islam in this way, does the Qur’an explicitly present it as a central, defining purpose of revelation itself?

I am glad you asked.

There are two types of ayat in the Qur’an, and Allah (swt) makes this distinction Himself:

“He is the One Who has sent down to you the Book. In it are verses that are clear — they are the foundation of the Book — and others are ambiguous. As for those in whose hearts is deviation, they follow what is ambiguous in it, seeking fitnah and seeking its interpretation.” Quran (3:7)

Almost everyone knows one of these clear verses: “We did not create mankind and jinn except to worship Me.” (Qur’an 51:56)

This ayah leaves no room for reinterpretation or debate. We cannot claim He meant something else, or that worship refers to a different being, or that the command is metaphorical. Its clarity is deliberate, making it one of the foundational pillars of our religion.

But there is another core ayah of equal clarity yet far less known:

“We sent the messengers with clear signs, the scriptures and the balance so people could uphold…”

Before we complete this verse, notice what has already been stated. “Messengers” is plural. This refers not only to our Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) but to every prophet sent across human history; 124,000 prophets. “Scriptures” is also plural, encompassing the Qur’an as well as previous revelations like the Torah and the Gospel.

In other words, what we are about to read is not the purpose of one prophet or one book—it is the universal purpose of all prophets and all scriptures.

Now we can complete the ayah:

“We sent the messengers with clear signs, the scriptures and the balance so people could uphold justice.” Quran (57:25)

When we connect this verse to everything we’ve discussed so far, the picture becomes undeniable. Allah (swt) is not framing justice here as a recommendation, a by-product, or a secondary outcome of faith. He is presenting it as the explicit objective for which every prophet was sent and every scripture revealed.

In Islam, worship is not confined to rituals on the prayer mat. It is holistic, encompassing every action, word, and intention done in obedience to Allah (swt). From this perspective, the implementation of justice is not separate from worship; it is its highest manifestation in the public sphere. Justice is Tawḥid in action—the societal form of recognising Allah’s sole right to authority, and the practical dismantling of all false hierarchies and systems of oppression.

We often speak about Tawhid as the highest priority in Islam—and it is. But what we rarely emphasise is that Tawhid is not fulfilled by declaration alone; it is fulfilled through justice. Tawhid is the root, and justice is the fruit it must produce. A proclamation of the Oneness of Allah (swt) that does not translate into the establishment of justice is an incomplete expression of that very belief.

This is why Ibn Taymiyyah powerfully states: “Allah will support a just nation even if it is non-Muslim, and He will not support an unjust nation even if it is Muslim.” Justice is the inevitable consequence of true belief. Without it, the claim to Tawhid becomes hollow.

Justice, then, is not an abstract ideal in Islam. It is the lived expression of Tawhid, the measure of our faith, and the reason prophets were sent and scriptures revealed. It is the moral spine of our worldview; the standard by which nations rise and fall.

And when justice is established, something profound emerges: peace.

Justice is the cornerstone of any thriving civilisation. It is the foundation upon which everything else rests, because where there is justice, there is peace. And where there is peace, people find the stability to grow, to build, and to flourish.

Peace cannot be imposed. It cannot be manufactured through treaties, slogans, or superficial gestures. Peace is the natural by-product of justice. This is why the Arabic root letters of Islam (sīn, lām, mīm) are the same as those of salām, peace. Islam produces peace because Islam establishes justice, both within the soul and throughout society. When life is aligned with divine order, peace is not an aspiration but an outcome.

This brings us to a crucial realisation: if justice is the outward expression of Tawhid, and peace is the fruit that grows from justice, then Islam is far more than a private religion. It is a comprehensive, civilisational worldview: a moral architecture designed to shape individuals, communities, and political and economic structures.

Which now leads us to the next question:

What does a civilisation built upon Tawhid actually look like?

And how do its spiritual, social, political, and economic dimensions all emerge from this central truth?

Islam as a Civilisational Worldview

When we understand that justice is the lived expression of Tawhid—and that peace naturally emerges from justice—a profound truth emerges: Islam is not a religion in the narrow, Western sense of the term. It is not a compartmentalised set of private rituals or spiritual doctrines confined to the individual. Islam is a complete way of life—a comprehensive worldview that binds together the social, political, economic, and spiritual dimensions of human existence.

This interconnectedness is the natural outflow of Tawhid. If Allah (swt) is One, then reality is not fragmented. The self is not fragmented. Society is not fragmented. Everything in Islam returns to a single organising principle: the Oneness of God. Thus:

The Islamic worldview functions as a civilisational blueprint.

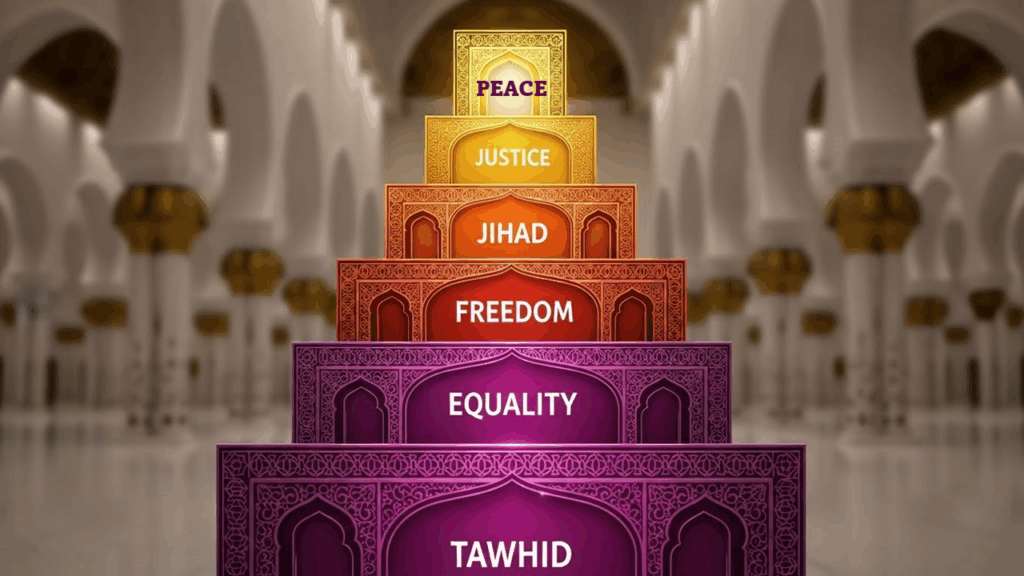

Tawhid sits at the centre, surrounded by the practical implications that flow from it—equality, freedom, jihad, justice, and peace—each forming a concentric circle that expands the scope of Tawhid from belief to behaviour, and from behaviour to societal structure.

![Start Here: Chapter 1 - The Islamic Worldview chapter 2 [auto saved]](https://ctrln.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Chapter-2-Auto-saved.jpg)

From that centre radiate four distinct pathways: the social, the political, the economic, and the spiritual, each shaped by the same moral architecture. Islam integrates these realms, ensuring they operate in harmony rather than contradiction.

With this framework we can begin exploring how it shapes every dimension of life. Islam does not separate the spiritual from the social, the political from the economic, or the personal from the collective; it is a coherent, interconnected worldview that defines how we understand reality, purpose, morality, and the human self.

To see this more clearly, we will walk through each of the four strands of the diagram—spiritual, social, political, and economic—and trace how they emerge from Tawhid and its practical implications. We begin with the spiritual dimension, the innermost domain of human experience, where the journey of identity, purpose, and consciousness takes root.

Spirituality Through A Tawhid-Centric Paradigm

Tawhid and the Question “Who am I?”

To begin exploring spirituality we must dive to the deepest depths of the self.

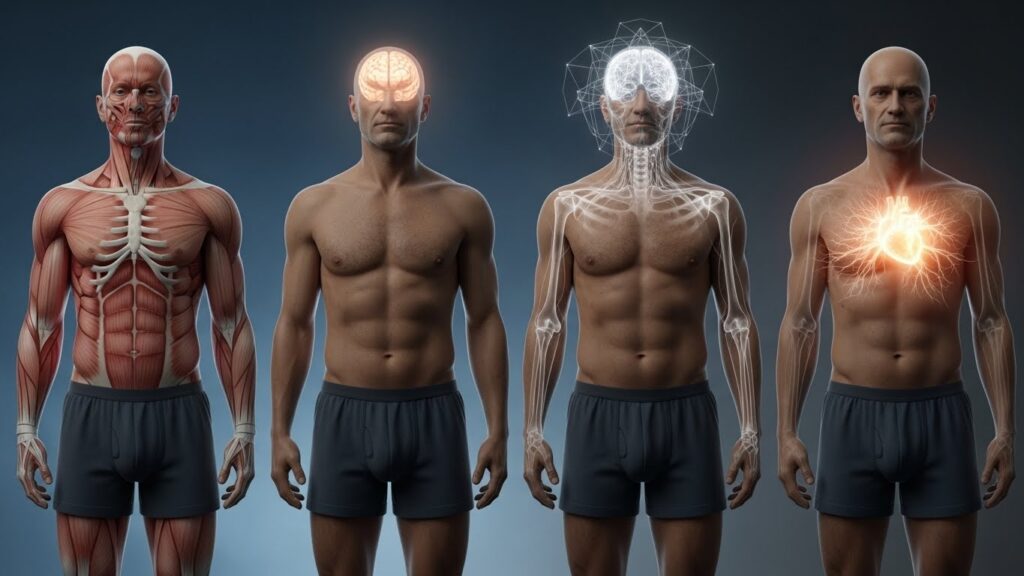

Have you ever paused to truly reflect on who you are? Not just the surface-level identity tied to your name, roles, or achievements, but the deeper question of your essence. Are you your body—the physical structure made up of tissues, muscles, and bones?

If so, consider this: if your finger were replaced, would you cease to be you? What about your entire hand? What if we went further and swapped your arm? At what point, if at all, would your sense of self change if we replaced your body, limb by limb?

If you’re not just your body, are you your brain? If technology advanced to the point of replicating your brain’s neurons, connections, and processes with synthetic materials, would your essence remain unchanged?

The brain itself functions much like a hard drive. It stores vast amounts of data—But ask yourself: does the storage define the content? Just as a hard drive is merely a repository for information, your brain collects and holds the raw material of your life. Yet, it does not interpret or create meaning from it.

This is where the mind comes into play. The mind processes the data stored in the brain, interpreting it based on your beliefs, assumptions, and paradigms. It is the lens through which you perceive the world, and this lens is shaped by your experiences, culture, upbringing, and even unconscious programming

But are you these beliefs, assumptions, and paradigms? If they change—as they often do throughout life—does your essence change with them? If your mind clings to a particular belief today but discards it tomorrow, are you not still you?

If the brain is the hardware and the mind the software, then what, if anything, is the user? What is the “I” that observes the mind’s thoughts and decides whether to act on them?

Now shift your focus outward. Consider the roles you inhabit and the external markers you associate with your identity. Are you your wealth, possessions, or job title? Does the degree hanging on your wall, the car in your driveway, or the house you live in truly define you? These are all things society holds up as symbols of success, but can they capture the depth of your essence?

What happens when these markers are taken away—when wealth fades, possessions lose their appeal, or job titles are no longer relevant? Do you cease to exist, or does your essence remain untouched by these external fluctuations?

If the body ages, the brain rewires, and the mind evolves—if possessions, achievements, and roles all fade—then what remains constant? What anchors your sense of self amidst these transformations? Islam teaches that our soul (ruh) is the essence of who we are, a divine spark breathed into us by Allah (swt). Unlike the transient nature of the physical world, this eternal essence remains untouched by bodily decay, mental shifts, or material labels, grounding us in a reality far greater than these passing aspects.

This is the Tawhid layer of spirituality: Your true identity is not scattered across changing material pieces; it is anchored in one reality—that our origin and ultimate destination is to Allah:

“Indeed, to Allah we belong, and to Him we shall return.” Quran (2:156)

Equality of Souls: Spiritual Worth in Islam

Once the soul is recognised as the core, a powerful truth follows: all souls share the same essential worth.

Race, nationality, gender, income, and status are all external layers. They may shape our experiences, but they do not define our value in the sight of Allah (swt). The only thing that differentiates us is the quality of our hearts and actions.

The Prophet (pbuh) said:

“Indeed, in the body there is a piece of flesh. If it is sound, the whole body is sound; and if it is corrupted, the whole body is corrupted. Truly, it is the heart.”

— Sahih al-Bukhari (ḥadith 52) and Sahih Muslim (hadith1599)

That is the equality layer of the circle. Tawhid smashes every hierarchy built on skin, tribe, class, or passport. It also challenges the quiet inferiority many of us carry because of those same markers. In the sight of Allah (swt), what matters is not external markers of a material world but the orientation of your heart.

Freedom: The Amanah of Choice

If all souls are equal, what makes one rise above another? Choice.

This ability to choose is central to the spiritual nature of human beings, setting us apart from other creations. While we share characteristics with both animals and angels, we also possess attributes that set us apart from both.

Free will is the essence of what makes us human. Free will places humanity on a spectrum between the instinct-driven nature of animals and the disciplined obedience of angels. Animals are ruled by base desires, while angels exist in perfect submission to Allah (swt). We are the only creation asked to choose: to act in ways that either align with our fitrah (our innate disposition toward goodness) or our nafs (base desires).

Allah (swt) describes this as a trust:

“We offered the Trust to the heavens, the earth, and the mountains, yet they refused to undertake it and were afraid of it; but mankind undertook it…” Quran (33:72)

Every choice we make determines where we sit on the staircase:

- Higher, towards angelic qualities like patience, mercy, and submission, or

- Lower, towards animalistic qualities like greed, envy, and heedlessness.

This is the “freedom” layer of the circle where true freedom can be achieved because spiritual freedom in Islam is not the freedom to indulge every urge or desire, it is the freedom that comes from no longer being owned by anything other than Allah (swt). It is not primarily physical freedom, but an inner freedom—the freedom of the mind and the heart.

In practice, this means recognising that human beings are always in a state of servitude. The only question is to what. If we are not consciously submitting to Allah (swt), we will inevitably submit to something else often without realising it.

For many, that “something else” is material success. Decisions are shaped by money, status, and lifestyle. For others, it is social expectation—the need to be approved of, validated, or accepted. Some are driven by power and control, others by ego, desire, anger, or fear. These forces quietly dictate behaviour, priorities, and even moral compromises. This is dependence even if it is socially normalised.

To say lā ilāha illā Allah is not only to reject idols of stone, but to reject every internal and external force that claims authority over us. This is how Islam reframes freedom entirely. When a person aligns themselves with Allah’s guidance, they begin to regain control over their choices. They can say no to impulses that harm them, no to pressures that distort them, and no to expectations that pull them away from who they are meant to be.

This is where fitrah (innate disposition) becomes essential. The fitrah already recognises what is right, what is excessive, and what is destructive. Freedom, then, is the ability to act in accordance with that inner moral compass—even when doing so is uncomfortable or costly.

A person who is spiritually free is not unaffected by temptation, pressure, or desire. Rather, they are no longer ruled by them. Their sense of worth is not tied to wealth, image, or power. Their decisions are not dictated by fear of people or attachment to outcomes. Their heart has a single point of orientation.

This is the freedom Tawhid produces: to belong entirely to Allah is to be released from everything else.

Jihad of the Soul: Peeling Back the Layers

Allah (swt) created you upon the fitrah—an innate disposition towards goodness and an inherent recognition of His Oneness. This fitrah is your truest essence. It is the pure starting point from which you were created, unburdened by distortion, aligned with truth, and naturally inclined towards Allah (swt).

At its core, the fitrah draws you towards purity, righteousness, and connection with your Creator. But as you move through life, that core does not remain untouched. Experiences begin to shape you. External pressures accumulate. And slowly, layers form around the fitrah.

Upbringing, environment, pain, trauma, cultural norms, societal expectations, and the constant noise of the world begin to wrap themselves around your true self. Over time, these layers pull you further from your emotional and spiritual centre, until you are no longer living from who you were created to be, but from what life has conditioned you to become.

Layer by layer, life happened.

- A word from a parent that shattered your confidence? That’s a layer.

- A culture that told you your worth lies in the approval of others? That’s another layer.

- A society that sold you the lie that success is measured by possessions, not peace? Another layer.

- The voice that tells you Allah’s mercy isn’t for you? It’s a layer.

- The guilt that says you’ll never be good enough? It’s a layer.

- The fear that keeps you chasing dunya for validation? Another layer

What feels like “this is just who I am” is often nothing more than accumulated response.

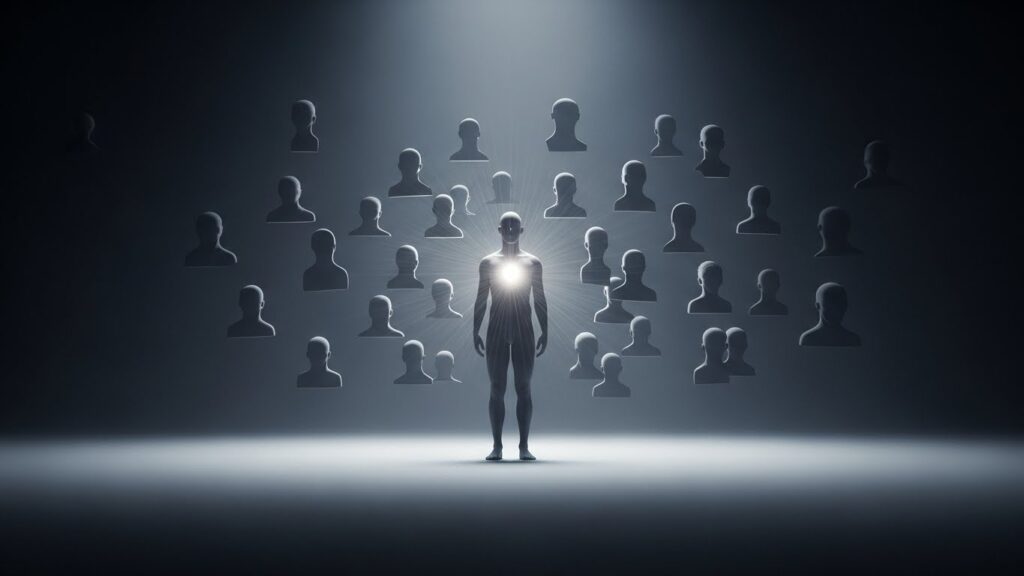

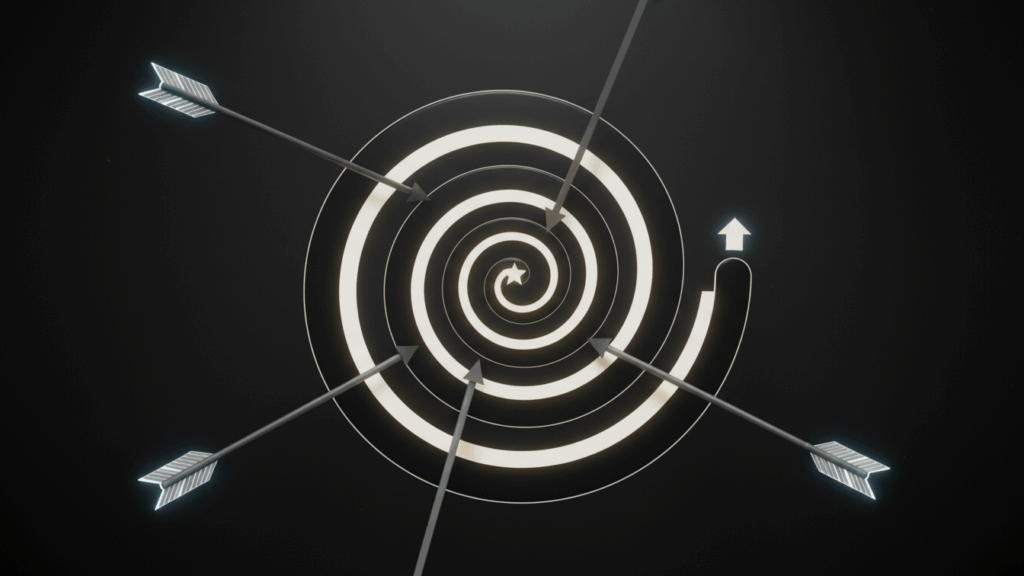

To understand this more clearly, let’s break this down with the aid of a visual:

At the very centre is your fitrah (represented by the star)—the pure, untainted essence of who you are. Surrounding it are layers formed by external influences: individualism, materialism, pain, fear, ego, cultural expectations, and societal programming. As the arrow of life moves outwards, layers form around your fitrah shaping how you see yourself and the world. Instead of responding from your core, you begin reacting from these external scripts.

The arrows represent guidance, truth, reminders, or even sincere advice trying to reach your fitrah. Some arrows never make it.

- One stops at the layer of individualism, where the self becomes the centre of everything.

- Another halts at the layer of pain, manifesting as defensiveness or withdrawal.

- Another gets trapped in materialism, tying a person’s worth to possessions or status.

None of these reach the core.

This is where the jihad of the nafs begins.

Inner jihad is not just a fight with Shaytan or about becoming someone new. It is about returning to who you were created to be. It is the ongoing struggle to peel back the layers that obscure the fitrah and realign your life with the moral and spiritual order Allah (swt) has already placed within you.

It is the work of unlearning, unburdening, and unbecoming—letting go of beliefs that no longer serve you, patterns born from pain, and identities shaped by fear—so that the soul can breathe again.

Paulo Coelho captures this idea well when he says:

“Maybe the journey isn’t about becoming anything. Maybe it’s about unbecoming everything that isn’t really you, so that you can be who you were meant to be in the first place.”

From an Islamic spiritual perspective, human fallibility is not a flaw in the system, it is part of the design. The Prophet (pbuh) said:

“By the One in Whose Hand is my soul, if you did not sin, Allah would replace you with a people who would sin and then seek forgiveness from Allah, and He would forgive them.”

(Sahih Muslim, 2749)

Our humanity is not measured by never falling, but by our willingness to recognise when we have drifted, repent, and return.

This is the essence of the jihad layer of the circle:

- A proper ordering of desire

- A commitment to continual return

- Self-awareness

- A daily effort to strip away what distorts us and live from the clarity of the fitrah

In this struggle, growth does not come from suppressing who we are, but from uncovering who we were always meant to be.

Inner Justice, Inner Peace

When we regularly check our ego, seek forgiveness, and choose our fitrah over our layers, something begins to settle inside. Thoughts, desires, and values fall into their rightful place. This is justice within the self—everything in balance, nothing in the wrong position.

Sayyiduna ‘Umar ibn al-Khattab (ra) once felt a trace of pride rise in his heart. To crush it, he stood in public and reminded people that he used to herd his father’s camels and be beaten for mistakes. He deliberately humbled himself so a layer of ego would not harden around his fitrah.

That is what inner justice looks like: refusing to let the nafs quietly rewrite the story.

Your soul is like a garden. The fitrah is the fertile soil. Gratitude waters it, dhikr feeds it, repentance removes the weeds. If you ignore it, weeds of arrogance, resentment, and desire overrun it. If you tend it, virtues grow almost naturally.

From this justice layer, a final state emerges: peace.

Not the peace of an undisturbed life, but the peace of a heart that keeps coming back to Allah (swt) no matter what life throws at it. That is the outer ring of the circle—sakīnah as the by-product of a just, Tawhid-centred inner world.

Living Spiritually From Your Fitrah

Seen through the Tawhid circle, spirituality is no longer a vague feeling; it is a structure:

- Tawhid: You are a soul, created by Allah, returning to Him.

- Equality: All souls share the same worth; only taqwā differentiates.

- Freedom: You have been trusted with choice between fitrah and nafs.

- Jihad: You strive to peel back layers and keep feeding the right “wolf”.

- Justice: You keep your inner world balanced through humility, tawbah, and realignment.

- Peace: Allah grants tranquillity to a heart that returns to Him: “Verily, in the remembrance of Allah do hearts find rest.” (Qur’an, Surah Ar-Ra‘d 13:28)

Just as Tawhid reorganises the inner life of the believer, it also reorganises the outer life of a community. The same circle that shapes the soul is meant to shape families, laws, economies, and power structures.

Having explored the spiritual dimension, we now widen the lens to see how this same Tawhid-centred framework unfolds across the political, economic, and social spheres. Here, Tawhid is no longer an abstract belief held in the heart alone, but an organising force that shapes authority, wealth, and human relationships in the real world.

Tawhid as the Organising Principle of Society

At the centre of the Islamic worldview stands Tawhid. Everything begins here. Islam does not first address institutions, markets, or states; it addresses the human heart, the soul (ruh), and the consciousness that recognises Allah (swt) as the sole source of authority, provision, and judgement. From this inner anchoring, the worldview expands outwards, shaping how the individual relates to Allah (swt) as well as to people, to power, and to wealth.

When the soul is anchored in Tawhid, a fundamental reorientation takes place. The individual no longer sees themselves as self-originating or self-owning. Their life, abilities, time, and outcomes are understood as entrusted rather than possessed. This is why Islam consistently dismantles the illusion of absolute ownership—of the self, of success, or of provision. From Allah we come, and to Him we return. That awareness does not remain abstract; it restructures how a person moves through the world.

From this inner grounding flows the social dimension. If all souls are created by the same Lord, then no human being can claim inherent superiority over another. Social hierarchies based on race, tribe, lineage, class, or status lose their moral legitimacy. Islam replaces fragmented identities with the Ummah. Belonging in Islam is not individualistic or transactional; it is responsibility-based. Rights exist, but they are inseparable from duties. A person does not simply ask what they are entitled to, but what they owe—to family, to neighbours, to the vulnerable, and to the wider community. Social life, then, becomes an extension of Tawhid, where relationships are governed by justice, mercy, and accountability rather than ego, reputation, or dominance.

This same logic expands into the political dimension. If Allah (swt) alone is sovereign, then ultimate authority does not belong to rulers, institutions, or the state itself. Power is not absolute; it is delegated, conditional, and accountable. Law is not merely the expression of human will, but must be measured against divine justice. Islam therefore does not sacralise rulers, nor does it permit obedience when authority becomes oppressive. The political order, in the Islamic worldview, exists to uphold justice, protect dignity, and restrain tyranny. Political legitimacy flows from moral alignment, not coercive strength.

The economic dimension unfolds in the same way. Just as the self is not owned, wealth is not owned in an absolute sense either. Provision belongs to Allah (swt), who distributes it according to His wisdom. What reaches a person is not proof of superiority, and what is withheld is not proof of inferiority. Wealth, therefore, is an amanah: a trust to be used responsibly, not a possession to be hoarded without consequence. Islam does not reject desire or material wellbeing; it regulates them. One is permitted to enjoy what Allah (swt) has made lawful, but that enjoyment is bounded by duty to others. Zakat, charity, inheritance laws, and the prohibition of exploitation are not peripheral rules; they are the economic expression of Tawhid. They ensure that wealth serves society rather than enslaves it.

What ties these dimensions together is the consistent movement outwards from the soul. The same Tawhid that liberates the heart from fear, envy, and ego also liberates society from hierarchy, politics from tyranny, and economics from exploitation. This is why Islam cannot be reduced to private spirituality, nor confined to ritual practice. It is a civilisational worldview, one in which inner alignment produces outer order.

And where this alignment is upheld, justice takes root. Where justice takes root, trust follows. Where trust exists, peace emerges as a natural outcome of life lived in accordance with divine order. This is the coherence of the Islamic worldview: one source, one moral logic, unfolding across every layer of human existence.

The Next Chapter: The Rise of Islamic Civilisation

When we understand the Islamic worldview, something becomes strikingly clear: the greatness of the Muslim world did not emerge from military power, wealth, or technology. It emerged because a civilisation finally aligned itself with the divine order, placing Tawhid at its centre, justice as its mandate, and human dignity as its constant.

Civilisations rise when they align themselves with deeper principles, values, and frameworks. History shows that many nations and empires, Muslim and non-Muslim alike, have risen when they upheld these principles, and declined when they violated them.

This is why understanding the Islamic worldview is so critical. It provides the lens through which we can recognise the underlying patterns that govern the rise and fall of civilisations. Without this lens, history appears random or purely material. With it, patterns begin to emerge that repeat themselves across time, geography, and culture.

In the next chapter, we will explore these principles more closely: the values that allow civilisations to grow, stabilise, and contribute to humanity, and the conditions that inevitably lead them to stagnation and collapse. We will examine how early Muslims embodied these principles in practice, and why their presence produced a civilisation capable of extraordinary achievement.

This is why The Missing Muslim Narrative is not a chronological history book. It is a conceptual map: A journey into who we are, why we rose as a civilisation, why we declined, how we arrived at this moment, and how we move forward from here.

Turn the page: The Rise of Islamic Civilisation.