Chapter 2: The Rise of Islamic Civilisation

In the previous chapter, we explored the practical implications of Tawhid and how it dismantled the oppressive systems that dominated Arabia. What followed was not merely the removal of injustice, but the deliberate construction of something entirely new. A foundation strong enough to transform a fragmented people into a civilisation that would influence the entire world.

And yet, here lies one of the great contradictions of our time.

Everyone will affirm that Islam is a deen. On paper, in theory, there is little disagreement. But in practice, we live and behave as if Islam is nothing more than a private belief system confined to personal morality and ritual observance.

A simple litmus test exposes this tension.

Ask almost any imam whether Islam is a deen, a complete way of life, and the answer will be an emphatic yes. But the moment the conversation turns to politics, power, governance, or systems, the response quickly becomes: “Brother, no politics in the mosque.”

What this reveals is a deep internal fracture. Islam is accepted as a deen in language, yet reduced to a religion in practice. It is affirmed conceptually, but neutralised operationally.

Before we can answer the question of what led to our rise, there is a prerequisite that must be confronted honestly.

The first step towards understanding the rise of Islamic civilisation is to truly understand that Islam is a deen—not as a slogan, not as a theological claim, but as a lived reality. This requires a conscious shift: moving Islam out of the theoretical realm and into the practical fabric of how we think, organise, govern, and act in the world.

As long as Islam remains something we affirm but do not operate by, revival will remain an abstract hope rather than a tangible outcome. Civilisations are not revived by intentions alone, they are revived when a people internalise a worldview deeply enough for it to shape their values, their institutions, and their collective behaviour.

Only once Islam is reclaimed as a lived civilisational framework, rather than a private spiritual and moral identity, can we begin to understand why Islamic civilisation rose because this reduction did not produce Islamic civilisation in the past—and it will not revive it today.

Exploring the rise of Islamic civilisation and what we often label the “Golden Age” is not about celebrating achievements for their own sake. Yes, those achievements matter. They are impressive. They restore confidence in an age saturated with Islamophobia, where Muslims are persistently portrayed as backwards, violent, or civilisationally inferior. That sense of pride is not trivial.

But if it stops there, it becomes nostalgia—a feel-good exercise with no power to transform our heart, mind, and civilisation.

What truly matters is not what Muslims achieved, but what those achievements were built upon.

Civilisations are not sustained by brilliance alone. They are sustained by values and principles. If revival is to be more than a slogan, then what we must anchor ourselves to is not history as spectacle, but history as instruction. We must internalise those values and principles—as a civilisation–rather than admire their outcomes from a safe distance.

This is why The Missing Muslim Narrative is not a chronological retelling of events, nor a simple catalogue of rulers, dates, and battles. On top of being concerned with what happened, it concerns with why it happened, how it happened, and what it produced. It is a conceptual understanding of our civilisational journey; where we came from, how we arrived here, and what direction remains open to us.

For this reason, the “Golden Age” of Islam cannot be confined to specific centuries or locations such as Córdoba or Baghdad. It is better understood as every moment in our history where Islamic principles were lived authentically and translated into meaningful contribution. Wherever those principles were present, something life-giving emerged.

And yet, this is precisely where many of us fall into a dangerous oversimplification.

Many Muslims today claim that the reason we are in the state we find ourselves in is because we do not pray salah properly. That if only we woke up for fajr, everything would change. This argument collapses the moment we engage even the slightest amount of logic.

If that were true, then Western civilisation would never have risen. Nor would any non-Muslim civilisation in history. No empire, nation, or society that did not wake up for fajr should ever have prospered—yet history clearly shows otherwise.

Just as the law of gravity applies to everyone, whether you are Muslim or not, there are universal principles that govern the rise and fall of nations. These principles operate regardless of belief. They are woven into the fabric of how societies function.

Whenever a people live by them, they rise. Whenever they abandon them, they decline.

Islam could only have risen to the heights that it did because it was never merely a personal religion. It was—and is—a civilisational blueprint. A deen.

Islam was never meant to produce pious spectators. It was meant to produce a civilisation anchored in justice, responsibility, and moral courage.

So the real question is not whether we pray enough, but whether we understand what actually makes a civilisation rise.

So, what exactly is it that makes a civilisation thrive?

Principle 1: Justice

Justice is the bedrock of any civilisation. Without it, no society can survive for long. In Islam, justice is the explicit objective of revelation:

“We sent the Messengers with clear signs, the scriptures, and the balance so people could uphold justice” (57:25)

This foundational standard set Islam apart, because justice is not one principle among many. It is the organising principle.

Every civilisation, regardless of its ideology or religion, ultimately rises or falls on how it deals with justice. In the early period of Islam, particularly under the Rashidun Caliphs, justice was applied universally, regardless of status or position. Ali ibn Abi Talib, while serving as Caliph, once stood in court alongside a Jewish citizen over a disputed shield. When Ali could not produce the required evidence, the judge ruled against him and Ali accepted the verdict without protest. Umar ibn al-Khattab could be challenged publicly by an ordinary woman and would accept correction when proven wrong. Governors who abused their power were held accountable or swiftly removed.

This uncompromising commitment to justice gave the new Muslim community immense legitimacy. People living under Muslim rule, whether Muslim, Christian, or Jewish, felt secure and protected. That security fostered cooperation within society, creating the stability required to build institutions, produce knowledge, and plan beyond the present moment.

Islamic civilisation rose because its moral architecture produced trust at scale. When justice was upheld, expansion was not merely territorial, but moral. People did not simply submit to Muslim rule; many accepted it because it was fairer than what came before. Taxation was regulated. Courts were accessible. Rulers were accountable.

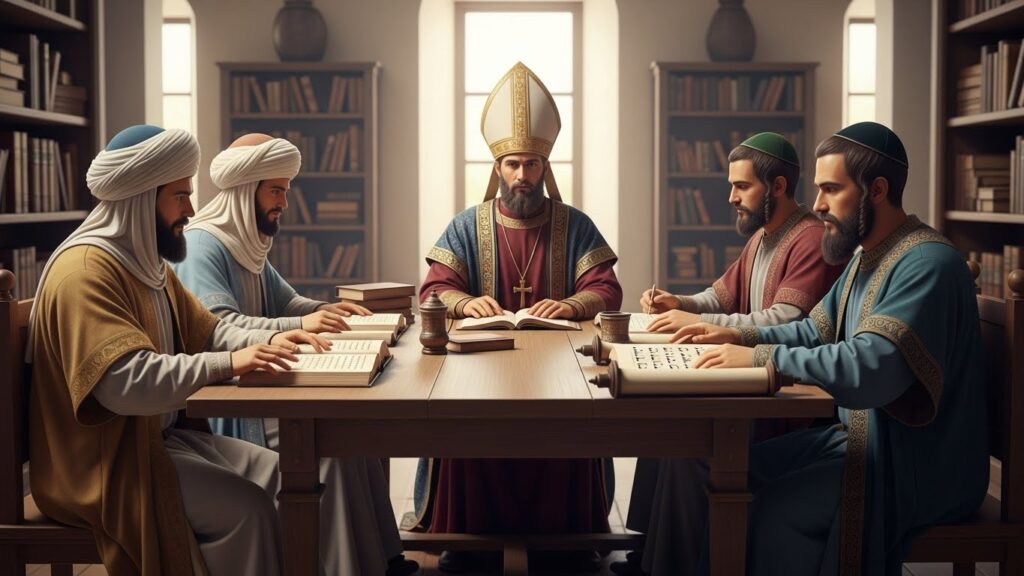

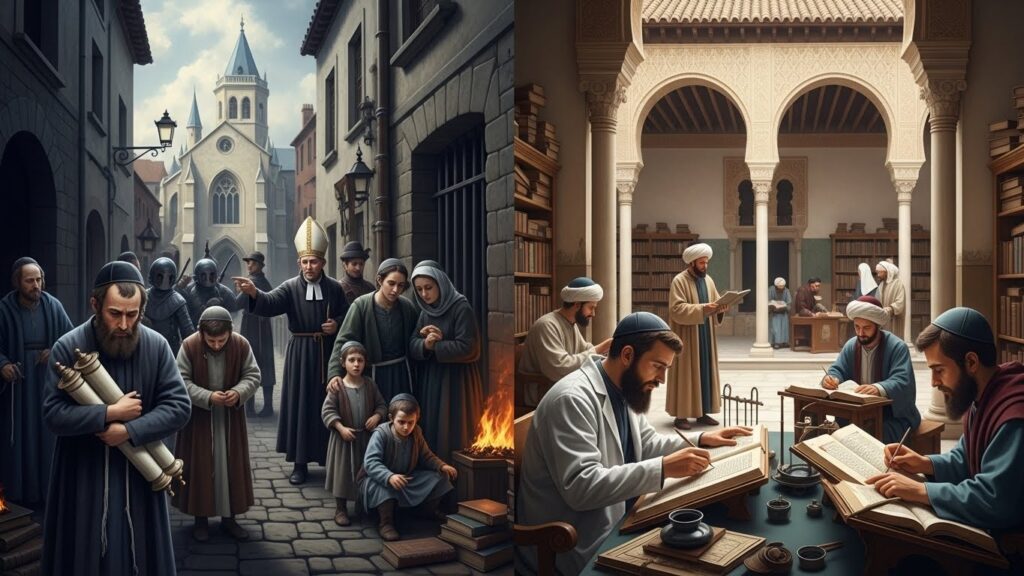

A powerful illustration of this can be seen in Córdoba and the wider conquest of al-Andalus. Visigothic Spain was marked by severe religious persecution, particularly against Jewish communities and non-Trinitarian Christians who fell outside the orthodox Church. The ruling order enforced theological conformity through coercion, leaving large segments of society marginalised and insecure.

When Muslim rule emerged, it did not replace one elite with another. It introduced a system where religious difference was tolerated, legal protections were extended, and communities were governed with a level of fairness they had not previously experienced. As a result, many did not resist Muslim rule because it represented a more just alternative to what came before.

This moral legitimacy laid the foundations for what later became known as Convivencia—a period in which, for the first time in European history, Muslims, Christians, and Jews lived side by side under a shared political order that protected religious difference rather than criminalising it.

This coexistence was the direct outcome of justice restraining power. Communities were allowed to retain their faith, their courts, their scholars, and their internal affairs, while participating in a broader civic framework governed by law. This created something rare in history: security without forced uniformity.

That security fostered cooperation within society, creating stability and giving people the mental and material space to think beyond survival

It is no coincidence that under this environment, al-Andalus became one of the greatest centres of learning the world had ever seen. Libraries containing hundreds of thousands of volumes flourished. Scholars translated, preserved, critiqued, and expanded upon Greek, Persian, Indian, and earlier Islamic knowledge, whilst rigorous engagement between Muslim, Christian, and Jewish thinkers sharpened intellectual traditions rather than silencing them. Education was woven into the fabric of society.

Crucially, this environment also produced what many historians refer to as a Jewish Golden Age. Under Muslim rule in al-Andalus, Jewish communities experienced a level of security, intellectual freedom, and social mobility that was almost entirely absent elsewhere in medieval Europe. Jewish scholars rose to prominence as physicians, poets, philosophers, and administrators. Hebrew grammar was systematised. Jewish philosophy flourished through engagement with Islamic thought.

The principle of justice as the engine of civilisational rise can also be observed beyond the Muslim world. Medieval Europe was once suffocated by absolute monarchy and unchecked church authority. Over time, it became clear that even rulers had to be bound by justice. The Magna Carta marked a turning point by forcing the English king to accept that he was not above the law. This principle—that justice must restrain power—later became the seed for constitutional governance, parliaments, and legal systems.

The Enlightenment did not invent justice; it formalised it into institutions. Those institutions created relative stability and trust in governance, enabling scientific progress, economic coordination, and long-term planning.

The lesson is simple and unavoidable: justice is not a luxury or a moral ornament. It is a law of civilisation, as real and unbreakable as gravity. When it is upheld, societies flourish. When it is institutionalised, trust compounds. And when it becomes the organising principle of a people, it produces civilisational momentum.

Principle 2: Accountability

Justice can only endure when power is restrained, and power is restrained through accountability.

Every civilisation that rises must solve the same structural problem: how to prevent authority from drifting into tyranny once it consolidates. Good intentions and personal piety are not enough. Without structures that hold people to account, justice becomes dependent on individual personality alone—and character, however noble, is not a system. A leader today may coincidentally be just, but without a system, there is no guarantee the next will be.

This is why legitimacy through consent, followed by accountability, matters. Authority must be granted, not seized, and once granted, it must remain answerable. The first four caliphs operated within this paradigm. Leadership was not inherited, nor imposed by force, but emerged through consultation and acceptance and was continuously subjected to public scrutiny.

In Islam, accountability is a public responsibility. Authority was understood as an Amanah, a trust, not a privilege to be enjoyed or inherited. Leadership was conceived as a burden with consequences, not a reward with perks. Those who held power were expected to answer to God in the unseen and to the community in the seen.

This understanding shaped behaviour from the outset. After the death of the Prophet (pbuh), leadership was not seized, campaigned for, or celebrated. In fact, Abu Bakr did not seek authority at all. Abu Bakr initially proposed others for the role, suggesting figures like ‘Umar ibn al-Khattab instead of himself.

When leadership ultimately fell upon him, his first public address was not a victory speech but a warning:

“I have been appointed over you, though I am not the best among you. If I do well, help me. If I do wrong, correct me.”

This pattern repeats across early Islamic leadership. ‘Umar feared authority. ‘Ali delayed accepting it. Many companions avoided public office altogether, not because they lacked capability, but because they understood that leadership meant standing before God with the weight of other people’s lives, rights, and suffering on one’s back.

This ethos is perhaps best captured by Umar ibn al-Khattab, who famously said:

“By Allah, if even a mule were to stumble in Iraq, I fear that Allah would question me about it: Why did you not make the road safe for it, O Umar?”

This level of self-accountability extending beyond humans to animals under one’s rule is unmatched across human history.

Caliphs delivered public addresses in which they explicitly invited correction. Rulers could be questioned openly without consequences. Officials were monitored, audited, and dismissed if they abused their power. The public treasury (Bayt al-Mal) was treated as communal property, not a ruler’s personal reserve.

When ‘Umar was questioned publicly about how he had acquired two pieces of cloth when others had received only one from the state distribution, he did not dismiss the challenge as disrespect. He clarified that his son had given him his share. The point here is the norm being established: leaders were expected to explain themselves.

This level of transparency mattered because power without visibility inevitably corrodes.

Where power operates without scrutiny, injustice does not require malicious intent—it emerges naturally. Accountability introduces friction into authority. It slows decision-making. It demands justification. It creates pauses where conscience can intervene. In doing so, it protects the vulnerable long before abuse becomes systemic or irreversible.

Accountability also reshaped the relationship between ruler and ruled. People were not treated as passive subjects whose role was obedience alone. They were engaged citizens in the health of the public order. The obligation to enjoin what is right and forbid what is wrong was not confined to private behaviour; it extended into public life. This is why speaking truth to power is framed as the greatest jihad in the well known hadith.

This produced something essential for civilisational growth: trust in leadership. When people believe that authority can be questioned, corrected, and removed, they invest in the system rather than retreat from it. They cooperate rather than resist. They plan for the future rather than hedge against abuse. Accountability, therefore, is the mechanism that makes long-term coordination possible.

“Those among the Children of Israel who disbelieved were cursed by the tongue of David and of Jesus, son of Mary. That was because they disobeyed and transgressed.

They did not forbid one another from wrongdoing that they committed. How evil indeed was what they used to do.” [5:78–79]

The condemnation here is not for committing the wrongdoing but for failing to stop it. Silence is treated as collective moral failure. This balance is what allowed justice to remain a lived reality rather than a rhetorical ideal.

Where justice sets the moral direction of a civilisation, accountability keeps it on course. Without it, even the most just principles erode quietly. With it, justice becomes resilient capable of surviving beyond individual leaders and moments of moral clarity.

This is why Islamic civilisation was able to scale. Accountability made justice durable. It allowed authority to expand without losing legitimacy, and institutions to grow without collapsing under corruption.

Accountability after the Rashidun did not disappear, but it became increasingly institutional rather than personal, and increasingly removed from the centre of political power. This allowed Islamic civilisation to scale but also planted the seeds of future fragility.

Principle 3: A Unifying Framework

Every civilisation needs a unifying framework, something that binds people together, legitimises authority, and channels their collective energy. Without such a framework, societies fracture into competing interests, and power dissolves.

For Muslims, this framework is Tawhid, the Oneness of Allah. Here is where Islam stands in contrast to modern Western society, which operates on the assumption that spirituality and worldly success exist in tension with one another. Tawhid does not divide life into “religious” and “worldly” spheres. It integrates the spiritual and the material into a single, coherent way of life. Worship is not confined to the mosque. Earning a livelihood, governing with justice, building infrastructure, or seeking knowledge—all of these are acts of worship when aligned with Allah’s commands. This balance gave Muslim civilisation its unique strength. Our merchants were worshipping Allah (swt) through honesty in trade just as much as scholars teaching Qur’an; rulers who governed justly were engaged in ibadah alongside those praying in the mosque. This unity of purpose allowed our societies to be at once deeply spiritual and materially advanced.

The law of civilisation is universal: every society needs a framework, but it does not have to be spiritual. The Mongols rose to dominate the world through a different framework: sheer discipline, kinship ties, and a warrior ethos. The West rose by adopting secular rationalism and nationalism, sidelining the church and building a framework focused solely on material progress. These frameworks brought them immense worldly power, proving that civilisations can rise on many foundations.

But here is the difference. Frameworks that neglect the soul ultimately collapse or leave a void. The Mongols rose rapidly but their civilisation could not sustain itself. They partially assimilated into others but ultimately Islam was the only civilisation they adopted at scale as a complete governing framework.

The West rose through secularism and science, but at the cost of spiritual emptiness. Today, Western societies suffer crises of meaning—collapsing family structures, rising nihilism, declining birth rates, and widespread despair. The Western framework fuels power, but not peace.

Islam’s framework, rooted in Tawhid, is superior because it offers both: power in this world and meaning that carries into the next. On one side, it prevents spiritual escapism, as seen in some religious traditions such as forms of Buddhism, a retreat into personal piety that abandons responsibility for the world. On the other, it prevents material domination through a fixation on power and progress stripped of moral restraint. Tawhid holds both impulses in check by subordinating them to a higher purpose.

The Qur’an captures this balance perfectly:

“But seek, through what Allah has given you, the home of the Hereafter; and [yet], do not forget your share of the world” (28:77).

This balance explains why early Muslims were neither monks nor empire-builders in the conventional sense. This was recognised even by Byzantine observers. One such account describes a soldier who encountered the Muslims and later remarked, “By night they stand in prayer like monks, and by day they ride forth like warriors.”

What unsettled Byzantine officials was not simply Muslim courage or numbers but that our spirituality did not produce withdrawal and our power did not produce intoxication.

This was not monasticism armed with swords, nor empire cloaked in piety. It was a unified way of life in which worship refined character, character disciplined power, and power was exercised with purpose rather than excess.

That is the civilisational significance of Tawhid as integration. The early Muslims did not oscillate between heaven and earth or choose between the two. They lived within a single moral universe, where devotion deepened responsibility towards society rather than neglecting it.

When a civilisation shares a single moral framework that integrates belief, purpose, and action, it produces a collective identity. Tawhid did not only align the individual with Allah (swt); it aligned individuals with one another. It dissolved tribal, ethnic, and social divisions by subordinating all loyalties to a higher unity. From this shared moral universe emerged something essential for civilisational rise: unity and social cohesion. We now turn to this transformation: from fragmented tribes into a single Ummah

Principle 4: Unity & Social Cohesion

No civilisation rises through individual geniuses alone. It rises when people are able to act together. Every civilisation that has risen has been bound together by a shared organising belief, whether moral, ideological, or material. Without such a unifying force acting as the social glue, collective energy dissipates into internal rivalry, tribal competition, and zero-sum conflict. Talent fragments. Resources are wasted. Power collapses inwards.

Unity in Islam is built on shared submission to Allah (swt), which practically translates into people being bound to truth and moral responsibility. Tawhid dismantled every competing claim to ultimate loyalty and replaced it with a single organising identity: the Ummah. The older identities of tribe, race, and status were not necessarily erased but relativised. What mattered most was no longer who you were born as, but what you stood for.

“O mankind, We created you from a single male and female and made you into nations and tribes so that you may know one another. Indeed, the most noble of you in the sight of Allah is the most righteous of you. Surely Allah is All-Knowing, All-Aware.” Qur’an (49:13)

This shift produced one of the most radical social transformations in history. Former enemies prayed shoulder to shoulder. Masters stood beside former slaves. Arabs followed non-Arabs, and elites were corrected by the poor.

At the most basic human level, unity begins with safety. No group can function, let alone rise, if its members feel exposed, disposable, or alone. Islam created a profound sense of psychological and physical safety through the concept of the Ummah. To belong to the Ummah was to know that your dignity mattered, your life mattered, and your suffering would not be ignored. The Prophet (pbuh) described the Ummah as a single body: if one part is in pain, the entire body responds. This was not metaphorical poetry; it was a lived expectation. A Muslim could speak, strive, and struggle knowing that their people had their back. That sense of belonging generated deep bonds of loyalty and identity, replacing fear with confidence and isolation with collective strength.

From that safety emerged vulnerability and trust. When people know they are protected, they are willing to take risks together. They speak the truth. They stand for justice. They sacrifice comfort for principle. Islamic unity was built on this mutual responsibility. To enjoin good and forbid wrong is to care for the body as a whole. This is why early Muslims did not operate as disconnected individuals pursuing private success. They operated as a moral collective, where each person felt responsible for the state of the whole. That shared vulnerability produced a level of cooperation that no contract or coercion could replicate.

Above all, unity was sustained by shared purpose. The Ummah was bound together to fulfil a moral mission. What mattered was not that individuals achieved glory, but that the Ummah lived up to its responsibility before Allah (swt). This shifted ambition away from ego and towards contribution. The top-performing teams in the world understand this instinctively: success comes from cooperation rather than competition. The extra pass mattered more than personal recognition. Individual excellence was not erased, but it was directed towards a collective goal. This is why Islamic civilisation could mobilise entire societies with limited resources. People were not driven by glory or profit, but by meaning. And meaning, when shared, becomes one of the most powerful forces in history.

This is why Islamic unity was uniquely expansive without being internally corrosive. It could incorporate Persians, Africans, Arabs, Berbers, and Turks without requiring them to erase who they were. Difference was not a threat to unity; injustice was. Islamic civilisation was able to mobilise rapidly, absorb diversity, and sustain cohesion across continents, a feat that has defeated many other civilisations built on narrower foundations.

A unified society can coordinate at scale. It can pool resources, coordinate labour, and absorb shocks without collapsing. People are willing to sacrifice short-term interest for long-term collective benefit because they see themselves as part of something larger than the self. Islamic civilisation did not rise because Muslims were the most numerous or technologically advanced at the outset. It rose because internal cohesion turned limited resources into disproportionate impact. When unity exists, effort compounds. When it does not, even abundance fails to produce power.

Unity and social cohesion are a universal principle. It can be organised around many factors. The Roman Empire forged unity through loyalty to Rome itself—a shared political identity backed by military discipline and law. Citizenship, order, and obedience to imperial authority became the binding force that held together diverse peoples across vast territories.

Modern Europe offers a different model. Nation-states were organised around nationalism; a shared language, culture, and imagined collective destiny. National identity replaced tribe and dynasty as the primary source of loyalty. This produced immense mobilisation power, allowing states to industrialise, centralise authority, and project influence globally.

In the twentieth century, other ideologies played a similar role. Communism united populations around class identity and historical struggle. Liberalism bound societies through individual rights, markets, and national institutions. In each case, unity was achieved by subordinating competing identities to a higher organising idea. Civilisation always demands a loyalty that sits above the self.

Principle 5: Strong Institutions

Why institutions matter

Values that live only in hearts cannot sustain a society. Civilisation begins when political and economic structures that organise behaviour and distribute power are translated into institutions reflecting a civilisation’s ideological values and worldview.

Beliefs tell people what ought to matter. Institutions determine what actually happens, making them the mechanisms through which ideas become reality.

Institutions are not neutral containers. They encode a moral logic, an economic logic, and a power logic. They shape behaviour by rewarding certain actions and making others costly. They create patterns that people adapt to, often without thinking, normalising what once required moral effort. Over time, they produce a particular kind of society, regardless of the intentions of those within it.

Institutions determine whether wealth circulates or concentrates, whether people cooperate or compete destructively, and whether power is restrained or accumulates unchecked. A society that claims to value justice but builds institutions that reward exploitation will always produce injustice, regardless of how sincerely people speak about morality.

This is why civilisations do not rise simply because they produce virtuous individuals. They rise when they design systems that make virtue practical and make injustice difficult. When institutions are aligned with a society’s moral vision, people do not need to be heroes to act ethically. Ordinary people, living ordinary lives, end up contributing to something extraordinary.

Conversely, when institutions are misaligned, even good people are forced into harmful behaviour. They cut corners. They comply with injustice. They adapt in order to survive. Over time, the system reshapes the person, not the other way around.

This is the deeper reason institutions matter. They are not just tools of governance. They are moral environments. They form the background conditions that determine whether justice feels natural or costly, whether cooperation feels safe or risky, and whether society rewards contribution or extraction.

Islam understood this reality early by building structures that reflected its worldview so that the moral vision of Islam could live beyond individual piety and survive the test of scale, time, and power.

Only once this is understood can we appreciate why Islamic civilisation focused so intensely on how markets were organised, how law was applied, how wealth moved, and how authority was restrained. Without institutions, values remain intentions. And intentions alone do not build civilisations.

Alignment: When Belief, Structure, and Life Point in the Same Direction

At this point, a deeper pattern becomes clear. Civilisational rise begins with alignment.

Alignment refers to coherence across the core layers of a society. It exists when a society’s worldview, values, institutions, and everyday behaviour point in the same direction. Worldview shapes how reality, purpose, and authority are understood. Values define what is considered right, wrong, honourable, or shameful. Institutions translate those values into law, economy, and governance. Behaviour reflects how people actually live, cooperate, and make decisions in daily life.

When these layers reinforce one another, civilisation becomes stable, scalable, and resilient. Cooperation extends beyond kinship. Trust becomes rational. Long-term planning becomes possible. When these layers contradict one another, society may still grow in size or influence, but it grows brittle. Tension builds beneath the surface, and cohesion depends on pressure rather than consent.

Alignment, then, is internal consistency. It is the condition in which what a society believes, what it rewards, and how its people live are not at odds with one another. This was the condition Islam established early on, before scale, before expansion, and before power.

Once alignment exists, institutions are no longer artificial impositions. They become the natural means of preserving coherence as society grows.

From Vision to Structure: The Madinah Blueprint

The city of Madinah was more than a spiritual refuge or a gathering of believers. It was the first consciously constructed Islamic society. A place where belief, law, economy, and governance were aligned from the outset.

The Prophet (pbuh) began by organising social, political, and economic life in a way that reflected the moral vision of Islam. One of the earliest and most revealing choices was the establishment of the mosque and the market as central institutions. Worship and economic life were placed side by side. This communicated a civilisational truth: spiritual life and material life were not opposing forces. They were meant to discipline and reinforce one another.

What emerged in Madinah was the beginnings of an institutional order. An order designed to solve a problem every civilisation eventually encounters: the problem of coordination.

Once Islam expanded beyond the small, face-to-face society of Madinah, the question became how to get thousands, then millions of individuals, families, clans, and towns across vast regions, each with their own interests and temptations, to move in the same direction without constant friction and collapse.

Civilisations are built when ordinary people can reliably cooperate with strangers, trade beyond their neighbourhood, plan beyond their lifespan, and submit their disputes to something higher than raw power. Without this, society remains small. It remains tribal.

That is also why institutions matter. Institutions solve the coordination problem by making certain behaviours predictable and repeatable. They turn values into defaults. They create a shared operating system for public life.

Islam did not produce a society held together by a single mechanism or moral appeal. It produced a layered institutional order, where different domains of life were stabilised simultaneously. Each layer served a distinct civilisational function.

First, there were legal institutions.

Islamic courts were routine mechanisms embedded into daily urban life. People appeared before judges over unpaid wages, disputed partnerships, damaged goods, inheritance conflicts, tenancy disagreements, and abuse by officials. These cases were ordinary, frequent, and procedural. Justice functioned as an administrative process, not a moral spectacle.

Judges operated within a recognised legal framework. They relied on documented contracts, witness testimony, prior rulings, and established legal doctrines. Decisions were recorded in court registers (sijillāt), which formed a cumulative legal memory for the city. Property transfers, debts, endowments, marriage contracts, and commercial agreements were formally logged, allowing claims to be verified years later. This continuity mattered because it detached rights from personal power and tied them to written proof.

Courts had jurisdiction over state actors. Governors, tax collectors, military officers, and market officials could be summoned, challenged, and ruled against. While enforcement varied across time and place, the legal principle was stable: authority did not place one beyond adjudication. This constrained abuse, officials knew their actions could be scrutinised through recognised legal channels.

The cumulative effect was structural reliability. Economic and social life rested on enforceable expectations: contracts would be honoured, property claims could be defended, and disputes would be resolved through known procedures. This allowed cities to grow dense and complex without descending into private enforcement, factionalism, or chronic instability.

Second, there were moral and regulatory institutions.

Ethical behaviour was not treated as a private matter of conscience. It was organised through inspection, regulation, and enforceable standards. The office of the muḥtasib functioned as a public regulator responsible for maintaining fairness, safety, and honesty in shared spaces, especially markets.

Market supervision was detailed and practical. Inspectors checked weights and measures using standardised instruments. They examined the quality of goods, from bread and grain to textiles and metalwork. False advertising, adulteration, short-weight selling, and price manipulation were actively policed. Violations triggered immediate correction, fines, confiscation, or temporary bans from trading. Regulation operated at the point of activity, not after harm had already spread.

Oversight extended beyond commerce. Urban regulations governed how buildings were constructed and used. Workshops producing smoke, noise, or waste were restricted from residential areas. Drainage systems, street widths, shared walls, and access paths were regulated to prevent harm between neighbours. Slaughterhouses, tanneries, and kilns were deliberately placed away from dense housing. These rules shaped the physical layout of cities in ways that reduced conflict and public health risks.

Under the Mamluk period in cities such as Cairo and Damascus, regulatory manuals specified acceptable materials, minimum quality thresholds, and graduated penalties for repeat violations. Regulation was codified, localised, and continuous. Compliance did not depend on exceptional piety but on visibility, inspection, and consequence.

The result was an environment where trust emerged structurally. Buyers did not need intimate knowledge of sellers. Neighbours did not need private enforcement. Moral behaviour was stabilised through systems that made harm costly and fairness normal.

Third, there were economic institutions.

These governed how wealth moved through society. Markets were treated as public infrastructure rather than private chokepoints. Trade was encouraged, but rent-seeking, hoarding, and monopoly were constrained. Wealth was meant to circulate through production and exchange, not accumulate through control of access. Prosperity expanded outwards rather than pooling upwards.

A defining feature of this economic structure was the preservation of the commons. Certain foundations of social and economic life were deliberately removed from private ownership and shielded from permanent enclosure—the privatisation of shared infrastructure in ways that allow wealth and control to accumulate indefinitely. These included mosques, markets, roads, water systems, caravanserais, and institutions of learning. Access was treated as a right of participation in society, not a privilege granted by wealth or power.

By protecting essential spaces from commodification, Islamic civilisation lowered the cost of entry into public life. People could trade, learn, worship, and travel without submitting to gatekeepers who controlled access for profit. This prevented infrastructure from becoming leverage, and leverage from becoming domination. The commons ensured that the foundations of civilisation remained broadly accessible across class, tribe, and region.

Alongside the commons stood another stabilising institution: the guild. Guilds organised economic life around professions. Competition was channeled towards skill, quality, reliability, and genuine contribution. People advanced by becoming better at their craft and more valuable to the community they served.

What was deliberately prevented was the form of competition that later became central to capitalism: undercutting prices until others collapse, hoarding tools or infrastructure to block new entrants, leveraging scale to eliminate rivals, or exploiting desperation to dominate a market. These behaviours are not accidents of human nature. They are the logical outcomes of systems that isolate individuals, push all risk downwards, all reward upwards, and prioritises hoarding over contribution.

In contrast, Islamic institutions structured economic life so that excellence was rewarded without allowing success to depend on the destruction of others. Reputation and accountability were collective. Cheating and exploitation carried real social consequences. Livelihoods became stable across generations, skills were preserved, and productivity increased without tearing the social fabric apart.

Fourth, there were welfare institutions.

At the heart of the Islamic institutional order was a simple insight: no civilisation can thrive without economic foundations that serve the whole society. Justice, knowledge, unity, and governance all require resources. Institutions cannot run on moral intention alone.

Islam addressed this through a combination of public law, regulated markets, and a uniquely powerful economic institution: the waqf.

The waqf was not charity in the modern sense. It was a permanent endowment dedicated to public benefit. Once an asset was placed into waqf, it could no longer be sold, inherited, or privately extracted from. Its purpose was fixed, and its benefit was communal. This single institution transformed how wealth functioned in society.

From the earliest period of Islam through to its most mature empires, and especially under the Ottomans, waqf institutions funded almost every aspect of public life. Education, healthcare, water access, roads, hostels, orphan care, widows’ support, and even funeral services were sustained through endowments. From the cradle to the grave, people interacted with institutions that reduced vulnerability and removed fear of destitution.

This mattered deeply. When basic needs are secured, people are free to think beyond survival. When education is accessible regardless of wealth, talent can surface from anywhere in society. When care for the poor is institutionalised rather than optional, dignity is preserved. The waqf system created economic breathing room for the population, which is a prerequisite for knowledge, creativity, and long-term planning.

Together, these layers formed an integrated system. No single layer could carry the weight alone. Remove one, and pressure would overwhelm the rest.

Islam produced institutions that translated its values into daily life. Law restrained power. Markets organised exchange. Welfare reduced volatility. Moral regulation shaped incentives. Stability and growth emerged through structure.

What emerged in Madinah was a working moral order. One that assumed human weakness, yet constrained its worst impulses. One that encouraged initiative, yet limited exploitation. One that aligned individual effort with collective wellbeing.

This is why Madinah matters as a blueprint. It shows that Islamic civilisation was constructed through deliberate institutional choices that reflected a clear worldview.

From this foundation, something crucial became possible. With stability, trust, and economic security in place, attention could towards the pursuit of knowledge.

Principle 6: The Pursuit of Knowledge

The rise of Islamic civilisation cannot be understood without understanding the central place of knowledge in Islam itself.

The first revelation of the Qur’an did not begin with prayer, law, or ritual but with a command to “Read in the name of your Lord who created” (96:1).

The creator of the heavens and the earths, of time and space, the All-Knowing and All-Seeing did not choose to begin with these words randomly or coincidentally. Allah (swt) chose it because knowledge is the gateway to faith, responsibility, and civilisation.

The Qur’an repeatedly links knowledge to moral responsibility, awareness, and elevation. Those who know are not described as equal to those who do not:

“Say, ‘Are those who know equal to those who do not know?’ Only people of understanding take heed.” (Qur’an 39:9)

Ignorance is not neutrality but a condition that leads to misguidance, injustice, and dependence. Knowledge, in contrast, is presented as a means of seeing reality clearly and acting within it responsibly. This is why the Qur’an repeatedly demands us to reflect, reason, and understand.

Islam never confined knowledge to a narrow religious domain. This is why classical scholars declared the sciences that sustain civilisation as communal obligation (fard kifayah); Medicine, mathematics, engineering, governance, agriculture, and the tools required to protect and organise society. If a sufficient number of Muslims pursued these sciences, the obligation was fulfilled; if they did not, the entire community shared in the sin.

This point is often missed today, but it is essential. The pursuit of knowledge in Islam was never merely about producing scholars of scripture. It was about ensuring that the Ummah was not dependent, vulnerable, or dominated. A community that cannot heal itself, build for itself, or defend itself has failed in its collective responsibility.

This understanding is reinforced in the Prophetic tradition. The Prophet (pbuh) said that “wisdom is the lost property of the believer, and wherever he finds it, he has more right to it.” Truth was to be sought wherever it existed and integrated without losing moral orientation.

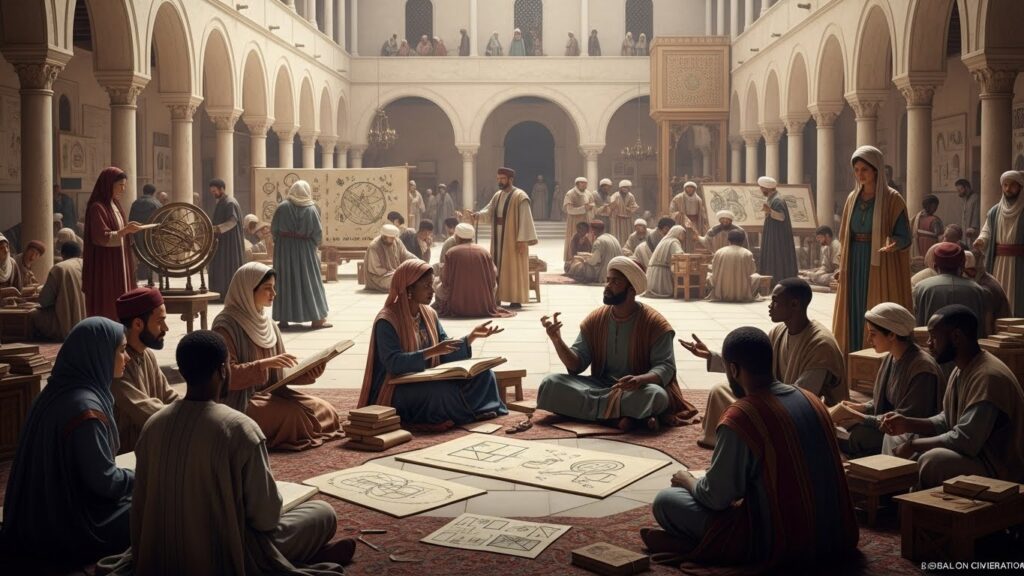

This is why Islamic civilisation engaged so confidently with existing knowledge traditions. Greek philosophy, Persian administration, Indian mathematics, and earlier medical sciences were neither rejected out of fear nor adopted uncritically. They were studied, refined, challenged, and developed further. Knowledge was not consumed passively but absorbed into an Islamic worldview that gave it direction and limits.

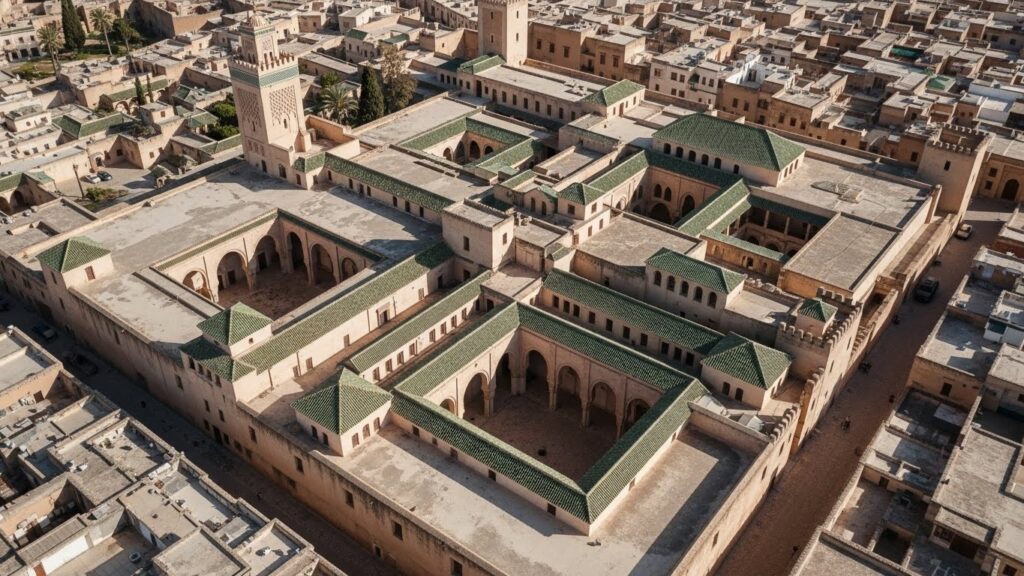

This framework explains why Islamic civilisation invested so heavily in learning institutions to organise, fund, and preserve knowledge. One of the most striking examples is the world’s oldest continuously operating university: University of al-Qarawiyyin, founded in the ninth century by Fatima al-Fihri. It reflected a civilisational understanding that education was a public good and a long-term investment. Institutions of learning were designed to outlast individuals and serve society across generations.

What made this possible was alignment across the entire civilisational structure. Justice created stability. Accountability restrained power. Unity generated trust. Institutions translated values into durable systems. Once this alignment was in place, education could be structurally funded rather than left to individual capability or patronage. From the early Abbasid period onwards, learning was increasingly supported through waqf and public funds, ensuring that it remained accessible, stable, and independent of individual rulers.

Over time, this support became fully systematised. Teachers were paid regular salaries. Students received stipends that freed them from the pressures of subsistence. Accommodation, food, books, and travel were often provided through endowments. Libraries were maintained as public infrastructure. Learning was not treated as a privilege for the wealthy or a favour granted by power, but as a social responsibility embedded into the fabric of society.

This system reached its most comprehensive expression under the Seljuks and was later perfected and expanded under the Ottomans, where education from childhood to advanced scholarship was sustained almost entirely through waqf. But the logic itself was much older. It emerged once Islamic civilisation understood that knowledge could only flourish when protected from volatility, politicisation, and economic exclusion.

This is the deeper civilisational insight. Knowledge flourished because the moral vision of Islam had already been translated into structures that made learning sustainable. When values align, institutions stabilise. When institutions stabilise, knowledge compounds. And when knowledge compounds, a civilisation rises not by accident, but by design.

When this understanding of knowledge was translated into institutions and culture, the results were transformative. Knowledge is the lifeblood of civilisation. Without it, societies stagnate; with it, they flourish and shape the world. When Muslims lived by this principle, we led the world in every field of human advancement. Under the Abbasids, Baghdad’s Bayt al-Hikmah, the House of Wisdom, became a global centre for translation, science, philosophy, and innovation. Muslim scholars preserved, refined, and expanded upon the knowledge of earlier civilisations. Literacy rates among the general population far exceeded those of contemporary societies. Ibn Sina (Avicenna) wrote medical encyclopaedias that remained standard references in Europe for centuries. Al-Khwarizmi developed algebra, a discipline whose very name comes from his book al-Jabr. Ibn al-Haytham pioneered optics and the scientific method centuries before Europe’s so-called “Scientific Revolution.” Andalusian Córdoba was described by European visitors as a city of light compared to the darkness of their own lands, where one city, Cordoba, possessed more books than the entire continent of Europe. Yes, a single city rivalled an entire continent. The scale of that comparison is difficult to overstate. Pause on that for a moment.

This explosion of knowledge came from a worldview that saw no contradiction between faith and reason, it was a paradigm that integrated the spiritual and so-called “worldly” aspects of life. To study the heavens was to reflect on Allah’s creation; to develop medicine was to serve humanity and earn His pleasure. Intellectual flourishing was tied to spirituality, making the pursuit of knowledge both a worldly necessity and a form of worship.

This understanding was explicitly articulated by the greatest minds of Islamic civilisation:

1. Imam al-Ghazali

“Knowledge is worship of the heart, the secret prayer of the soul, and the means by which one draws near to Allah.”

Al-Ghazali is explicit: learning is not preparation for worship, it is worship itself when pursued for truth and responsibility.

2. Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal

When asked how long one should seek knowledge, he replied:

“With the inkpot until the grave.”

For Imam Ahmad, lifelong learning was lifelong devotion, not a phase before “real” worship.

3. Imam al-Shafi’i

“Seeking knowledge is better than voluntary prayer.”

Al-Shafiʿi is asserting that knowledge sustains and protects all other acts of worship.

4. Ibn Taymiyyah

“Seeking beneficial knowledge is one of the greatest acts of worship, and it is obligatory according to one’s ability.”

He explicitly categorises learning as ʿibādah, governed by intention and obligation, not a personal preference.

5. Ibn al-Qayyim

“Knowledge is the life of Islam, the pillar of faith, and the light by which worship is guided.”

For Ibn al-Qayyim, worship without knowledge is blind action; knowledge gives worship its soul.

6. Al-Farabi

“The pursuit of knowledge is the highest form of human perfection, for through it one fulfils the purpose for which reason was given.”

Although framed philosophically, within the Islamic worldview al-Farabi understood reason itself as a trust from Allah, making its fulfilment an act of obedience.

7. Ibn Sina

In his writings on metaphysics and medicine, Ibn Sina repeatedly links knowledge to approaching truth and order, which he understood as reflecting divine wisdom. He regarded scientific inquiry as:

“A means of knowing the order Allah has placed in creation.”

For Ibn Sina, studying medicine or physics was not secular activity; it was reading the signs of Allah (swt) in the world.

8. Al-Kindi

“We should not be ashamed to acknowledge truth from whatever source it comes, even if it comes from nations distant from us.”

This reflects the Prophetic principle that truth belongs to the believer, and that seeking it is a moral duty.

9. Hasan al-Basri

“Knowledge is not by abundance of narration, but by light Allah places in the heart.”

Here knowledge is framed explicitly as a spiritual state—something granted, nurtured, and revered.

10. Imam Abu Hanifa

He described understanding law, commerce, and social dealings as:

“Part of understanding the religion.”

Meaning: knowledge of how society functions is part of worship, not external to it.

Civilisations reveal what they value through what they preserve, fund, and transmit. Islamic civilisation treated knowledge as infrastructure. Libraries were built like roads. Schools were endowed like markets. Scholars were supported through institutions rather than dependent on political favour alone.

The pursuit of knowledge, then, was one of its defining features. Islam rose not because Muslims happened to value learning, but because Islam made knowledge a duty, elevated its seekers, and embedded education into the fabric of society.

Rituals in Their Proper Place

At the beginning of this chapter, I challenged the notion that waking up for Fajr is a prerequisite for civilisational revival. At this point, a clarification is necessary. None of what has been described diminishes the importance of salah or ritual worship. On the contrary, it restores them to their proper place. In Islam, rituals are a means, not an end. Their significance lies not in their mere performance, but in how they transform the soul and shape our actions.

salah was never meant to function as a civilisational shortcut, nor as a substitute for justice, accountability, unity, or knowledge in the public realm. It trains consistency, remembrance, and moral restraint. But ṣalāh does not build courts, regulate markets, restrain rulers, or organise societies.

In this sense, salah is not a mechanism that changes a person or a civilisation by default. It has the potential to shape the inner world, but only when engaged with consciously. It is an opportunity for realignment and recalibration, not a guarantee of transformation. The perfection of salah does not lie only in correct recitation or posture. When performed with presence, it disciplines the ego, softens the heart, and reorients intention toward Allah (swt).

When rituals are divorced from their purpose, they risk becoming mindless routines, performed as a checklist or a mechanical step towards a perceived one-way ticket to Jannah. For many, rituals are treated as the purification process itself, rather than as the affirmations and recalibrations they were designed to be. The real purification of the heart takes place in the crucible of life itself, through how we behave, act, and respond to trials, injustice, power, and temptation. It is not forged on the prayer mat, but under the heat and hammering of responsibility, much like a weapon is strengthened through fire and blows.

Islamic rituals exist to recalibrate us, repeatedly aligning our focus and intentions toward Allah (swt). They anchor us in the values of our fitrah: truth, justice, patience, humility, and responsibility. When approached with sincerity, they bridge inner conviction with outer action.

This is why the early Muslims did not mistake worship for withdrawal, nor devotion for passivity. Their rituals produced people capable of justice. They were not used as a shield to excuse believers from their wider social and political responsibilities, but as a source of strength to fulfil them.

Principle 7: Resilience and Adaptability (Ijtihād)

Another universal principle of civilisational rise is adaptability. No society survives long if it cannot adjust to new realities. The ability to respond to challenges with resilience, and to innovate in the face of change, is what allows a people to not only survive but thrive.

The early Muslims embodied this principle. Within a single generation, desert tribes who had little experience of governance or large-scale organisation transformed themselves into builders of cities, administrators of vast lands, and pioneers of law. They developed institutions, codified systems of governance, and created infrastructure to sustain expanding societies. This leap was extraordinary. It was only possible because they coupled sabr, patience and resilience in the face of hardship, with ijtihād—independent reasoning and creativity in responding to new circumstances.

While Tawhid fixed ultimate truth, Islam never froze human understanding of how that truth should be applied. There were 124,000 Prophets sent to mankind along with four books but the reason the Qur’an applies till the end of time is because it isn’t an exhaustive policy manual but also a set of established principles. This left space for human reasoning to operate within moral boundaries. That space is what classical scholars called Ijtihad.

Ijtihad allowed scholars to respond to new circumstances while remaining anchored to revelation. As societies expanded across cultures, climates, economies, and political realities, this flexibility proved decisive. A civilisation that stretched from Spain to Central Asia could not survive on rigid uniformity. It required principled adaptation.

This adaptability appeared everywhere. Administrative systems absorbed Persian, Byzantine, and local practices without surrendering ethical constraints. Urban planning, taxation, agriculture, and trade evolved in response to context rather than ideology alone. Legal schools developed different methodologies while remaining within a shared moral framework.

What mattered was not that every society looked the same, but that each reflected the same moral orientation. Unity was preserved at the level of values, not appearances. This prevented fragmentation while allowing creativity.

It is from within this framework that the four schools of law emerged, not as competing sects, but as parallel expressions of principled adaptability. Each school was rooted in the same Qur’an, the same Sunnah, and the same moral objectives, yet each developed distinct methodologies to address different social realities.

Abu Hanifa lived in Kufa, a cosmopolitan city shaped by trade, contracts, and diverse populations. His school prioritised legal reasoning, analogy, and consideration of public interest. This made it particularly suited to complex commercial societies and later to large empires like the Abbasids and Ottomans, where governance required flexible legal tools without abandoning moral limits.

Malik ibn Anas, based in Madinah, treated the lived practice of the people of the city as a source of law. His methodology reflected a society where Prophetic precedent was embedded into daily life. This made the Maliki school especially effective in regions like North and West Africa, where social customs and communal continuity played a central role.

Muhammad ibn Idris al-Shafi’i responded to growing legal diversity by systematising the principles of jurisprudence itself. He clarified how the Qur’an, Sunnah, consensus, and analogy should be weighed, providing a disciplined framework that reduced arbitrariness. His school spread across East Africa, Egypt, and Southeast Asia, offering consistency in diverse cultural settings.

Ahmad ibn Hanbal emphasised textual fidelity in contexts where political authority risked distorting religious law. His approach functioned as a moral anchor, reminding society that adaptability must never slide into convenience or capitulation to power.

What is crucial here is not the differences themselves, but what they represent. The existence of multiple schools did not fragment Islamic civilisation. It stabilised it. Unity was preserved at the level of principles, while diversity was allowed in application. The law could respond to different economic systems, cultures, and political realities without requiring uniformity in every detail.

This is what living adaptability looks like. Not constant reinvention, and not rigid repetition, but faithful application under changing conditions. The four schools demonstrate that ijtihad was institutionalised, normalised, and transmitted across generations as a civilisational asset.

This capacity for renewal protected Islamic civilisation from brittle decline during its periods of strength. It could absorb shocks, govern new populations, and adjust to changing realities without losing coherence. Adaptability did not weaken the civilisation. It made it durable.

This resilience depended on everything that came before it. Without justice, adaptation becomes opportunism. Without accountability, flexibility becomes corruption. Without unity, diversity becomes fracture. Without institutions, renewal becomes chaos. Ijtihad functioned properly only within an aligned civilisational framework.

This is why adaptability appears at the end of the rise sequence. It is not a starting point. It is the outcome of a civilisation confident in its foundations.

Islamic civilisation rose because it was fluid within Islamic limits, mastering the balance between permanence and change. It knew what could not be compromised and what had to evolve.

But no civilisation collapses all at once. Decline begins when the principles that once reinforced one another start to fracture. Justice weakens. Accountability erodes. Unity gives way to division. Institutions decay. Knowledge becomes inherited rather than lived.

These universal principles, which once sustained a thriving civilisation, were gradually unravelled—leaving us exposed to colonialism—until the final political form was dismantled with ease by European empires in 1924.

This leads us to the next chapter of the Missing Muslim Narrative: The Decline of Islamic Civilisation.